Suggested Searches

- Climate Change

- Expedition 64

- Mars perseverance

- SpaceX Crew-2

- International Space Station

- View All Topics A-Z

Humans in Space

Earth & climate, the solar system, the universe, aeronautics, learning resources, news & events.

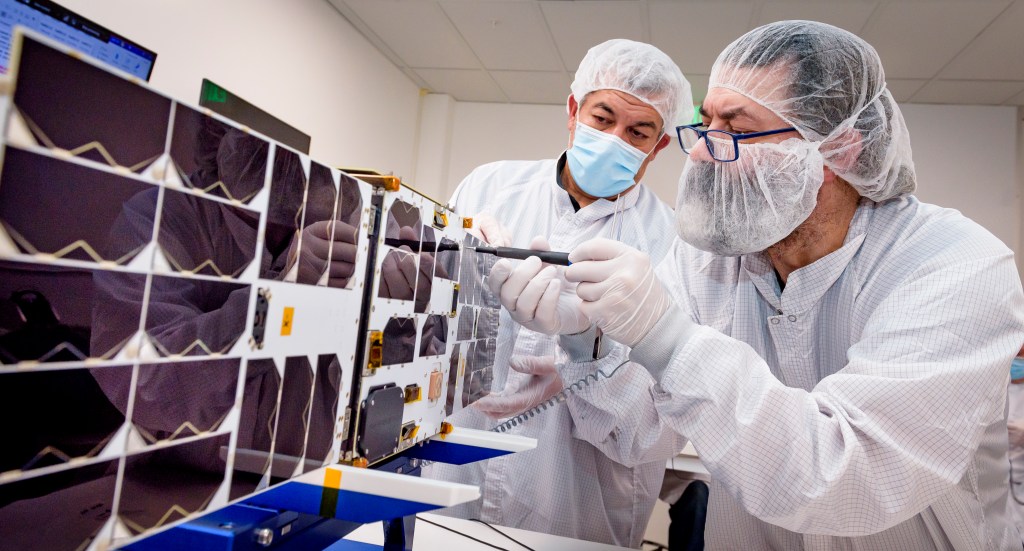

How NASA’s Lunar Trailblazer Could Decipher the Moon’s Icy Secrets

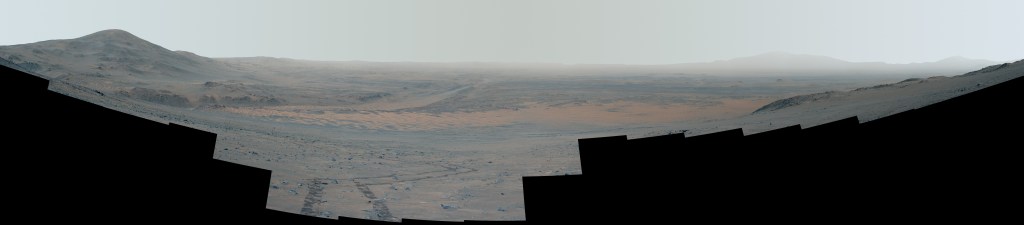

NASA’s Perseverance Rover Looks Back While Climbing Slippery Slope

What’s Up: October 2024 Skywatching Tips from NASA

- Search All NASA Missions

- A to Z List of Missions

- Upcoming Launches and Landings

- Spaceships and Rockets

- Communicating with Missions

- James Webb Space Telescope

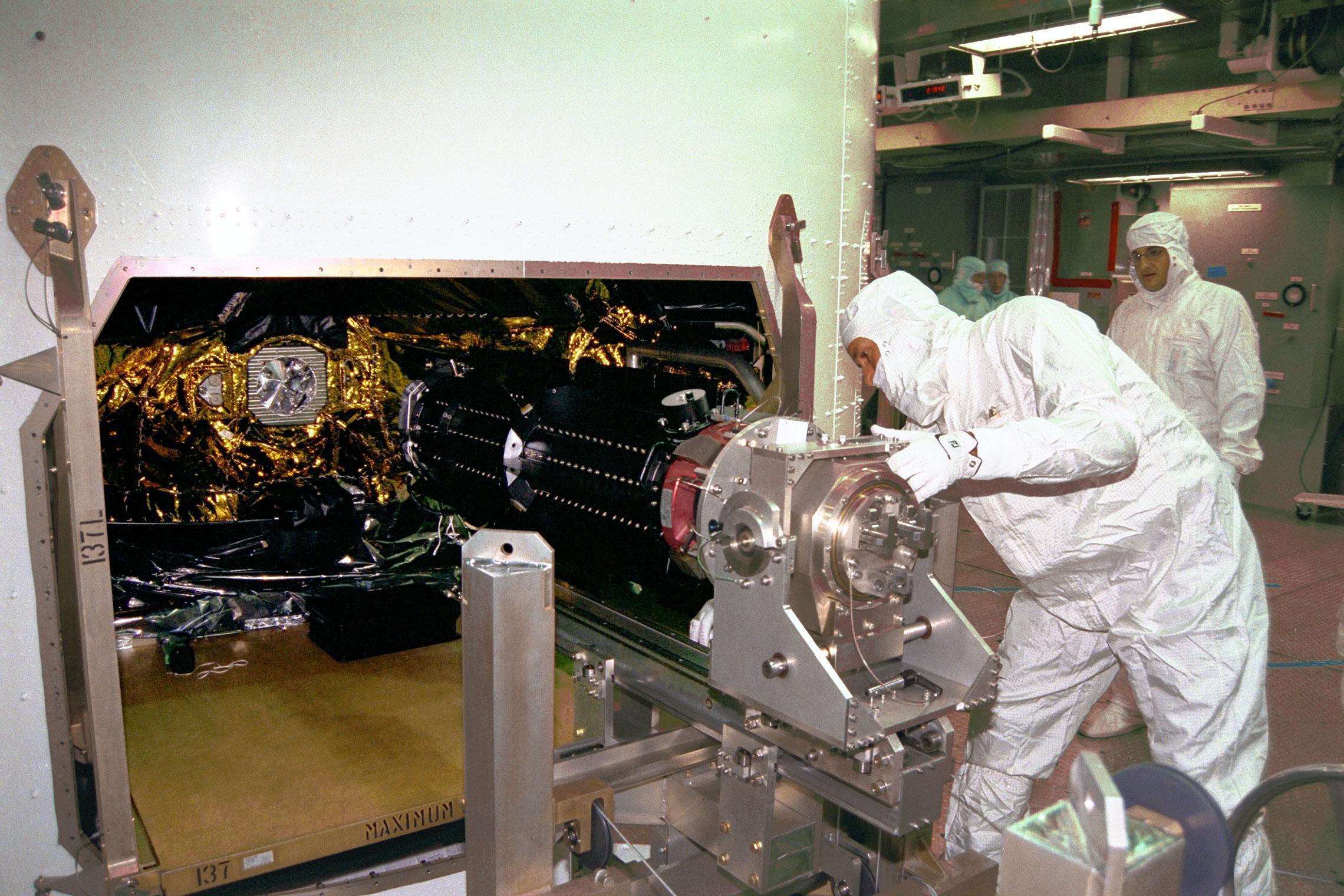

- Hubble Space Telescope

- Why Go to Space

- Commercial Space

- Destinations

- Living in Space

- Explore Earth Science

- Earth, Our Planet

- Earth Science in Action

- Earth Multimedia

- Earth Science Researchers

- Pluto & Dwarf Planets

- Asteroids, Comets & Meteors

- The Kuiper Belt

- The Oort Cloud

- Skywatching

- The Search for Life in the Universe

- Black Holes

- The Big Bang

- Dark Energy & Dark Matter

- Earth Science

- Planetary Science

- Astrophysics & Space Science

- The Sun & Heliophysics

- Biological & Physical Sciences

- Lunar Science

- Citizen Science

- Astromaterials

- Aeronautics Research

- Human Space Travel Research

- Science in the Air

- NASA Aircraft

- Flight Innovation

- Supersonic Flight

- Air Traffic Solutions

- Green Aviation Tech

- Drones & You

- Technology Transfer & Spinoffs

- Space Travel Technology

- Technology Living in Space

- Manufacturing and Materials

- Science Instruments

- For Kids and Students

- For Educators

- For Colleges and Universities

- For Professionals

- Science for Everyone

- Requests for Exhibits, Artifacts, or Speakers

- STEM Engagement at NASA

- NASA's Impacts

- Centers and Facilities

- Directorates

- Organizations

- People of NASA

- Internships

- Our History

- Doing Business with NASA

- Get Involved

NASA en Español

- Aeronáutica

- Ciencias Terrestres

- Sistema Solar

- All NASA News

- Video Series on NASA+

- Newsletters

- Social Media

- Media Resources

- Upcoming Launches & Landings

- Virtual Guest Program

- Image of the Day

- Sounds and Ringtones

- Interactives

- STEM Multimedia

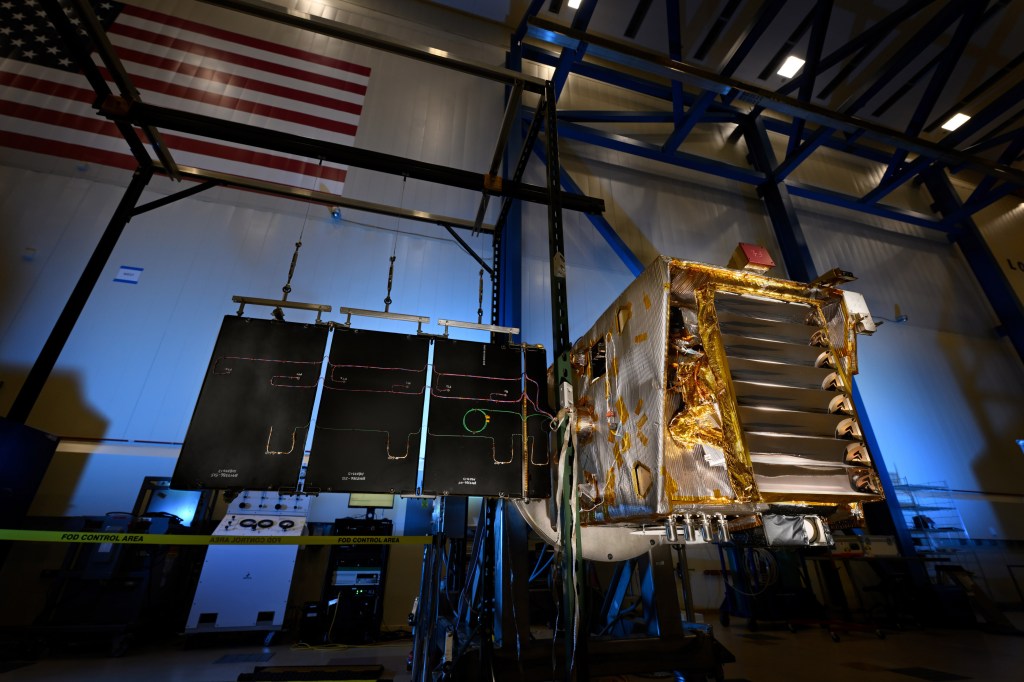

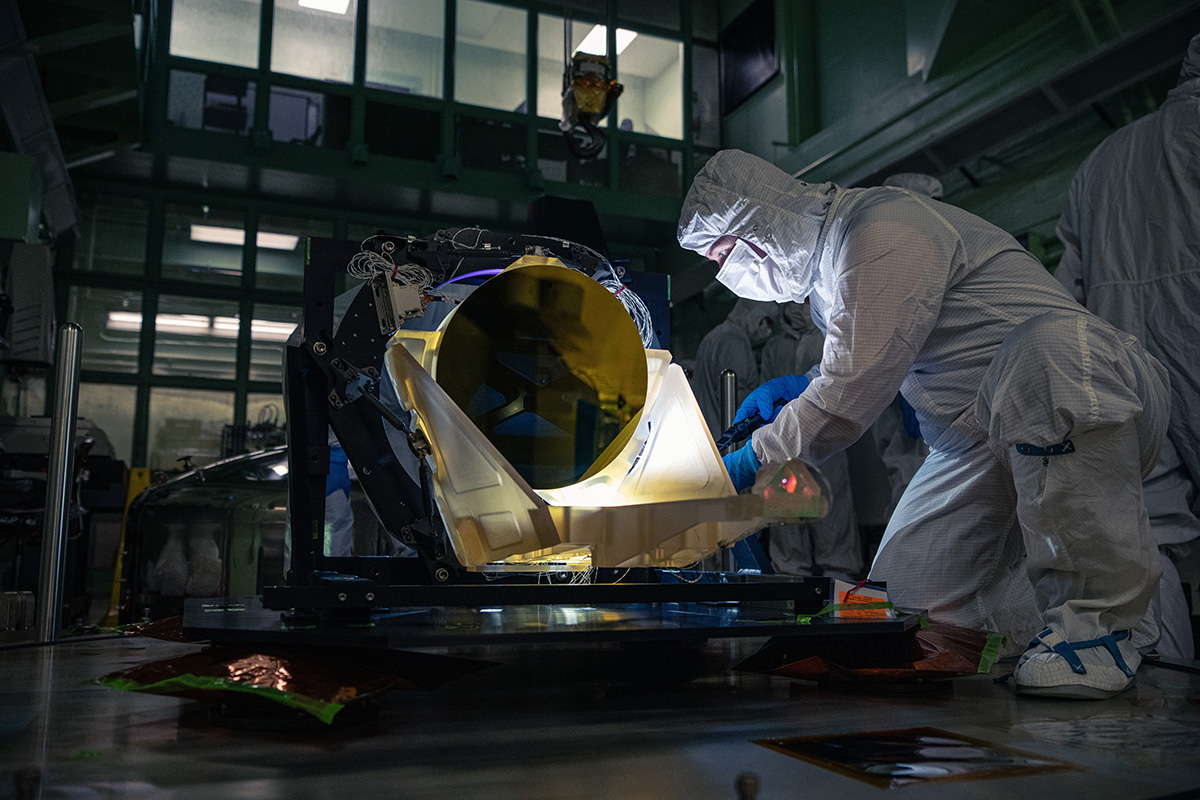

NASA Successfully Integrates Coronagraph for Roman Space Telescope

Station Science Top News: Oct. 25, 2024

Gateway: Centering Science

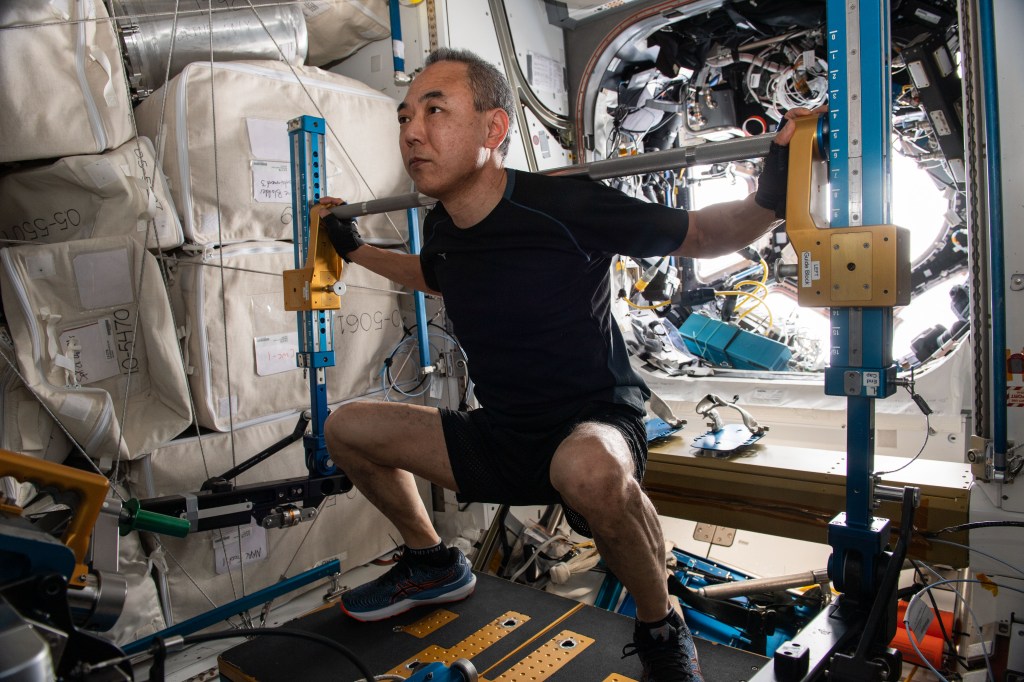

Risk of Reduced Cardiorespiratory and Musculoskeletal Fitness

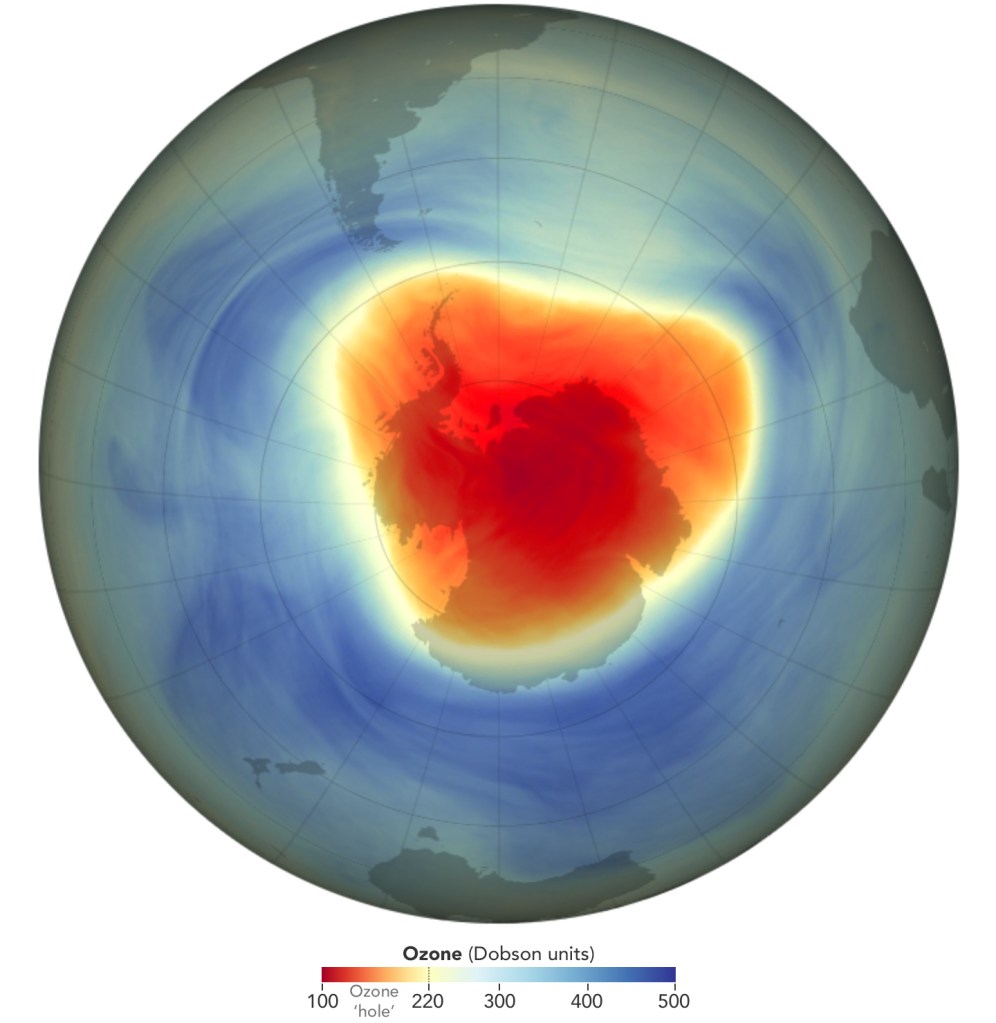

NASA, NOAA Rank 2024 Ozone Hole as 7th-Smallest Since Recovery Began

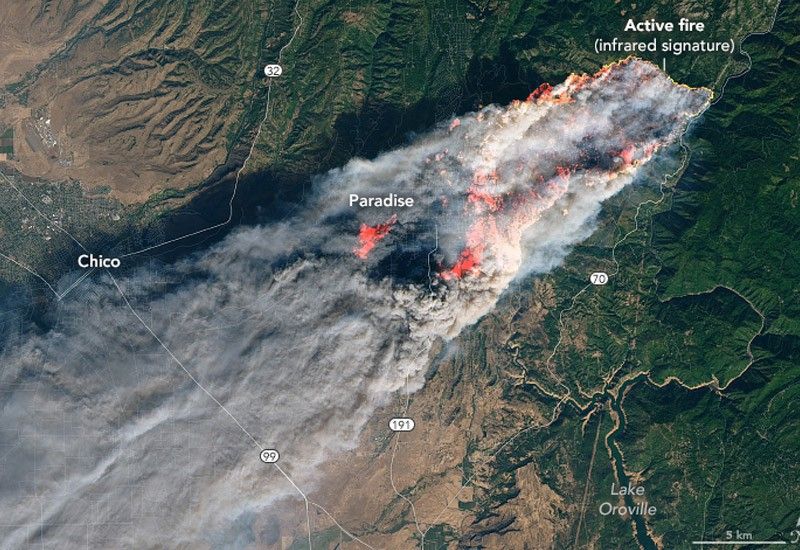

INjected Smoke and PYRocumulonimbus Experiment Expressions of Interest for No-Cost Participation / Contributions and Clarification of A.61 INSPYRE ST.

NASA Helps Find Thawing Permafrost Adds to Near-Term Global Warming

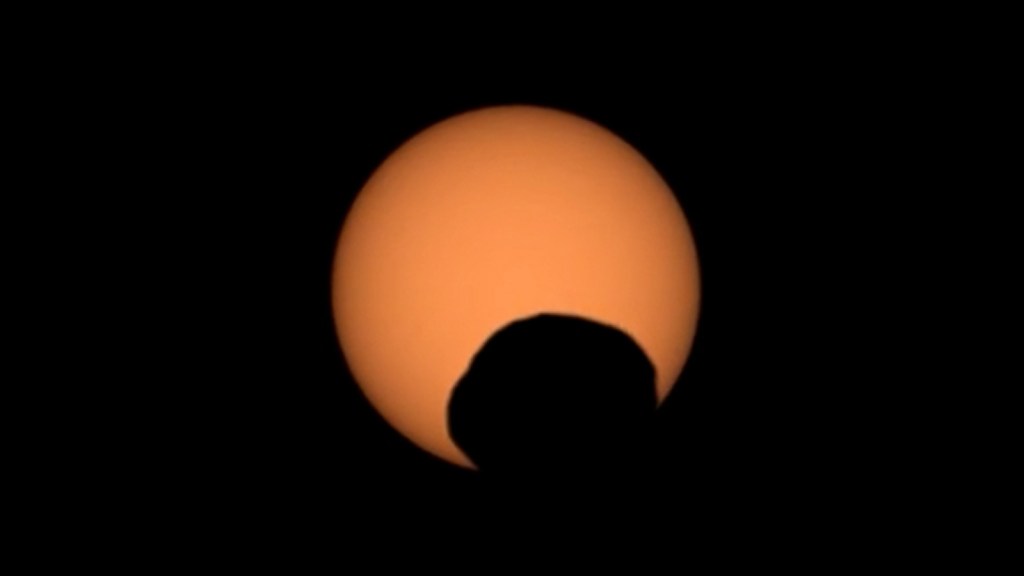

NASA’s Perseverance Captures ‘Googly Eye’ During Solar Eclipse

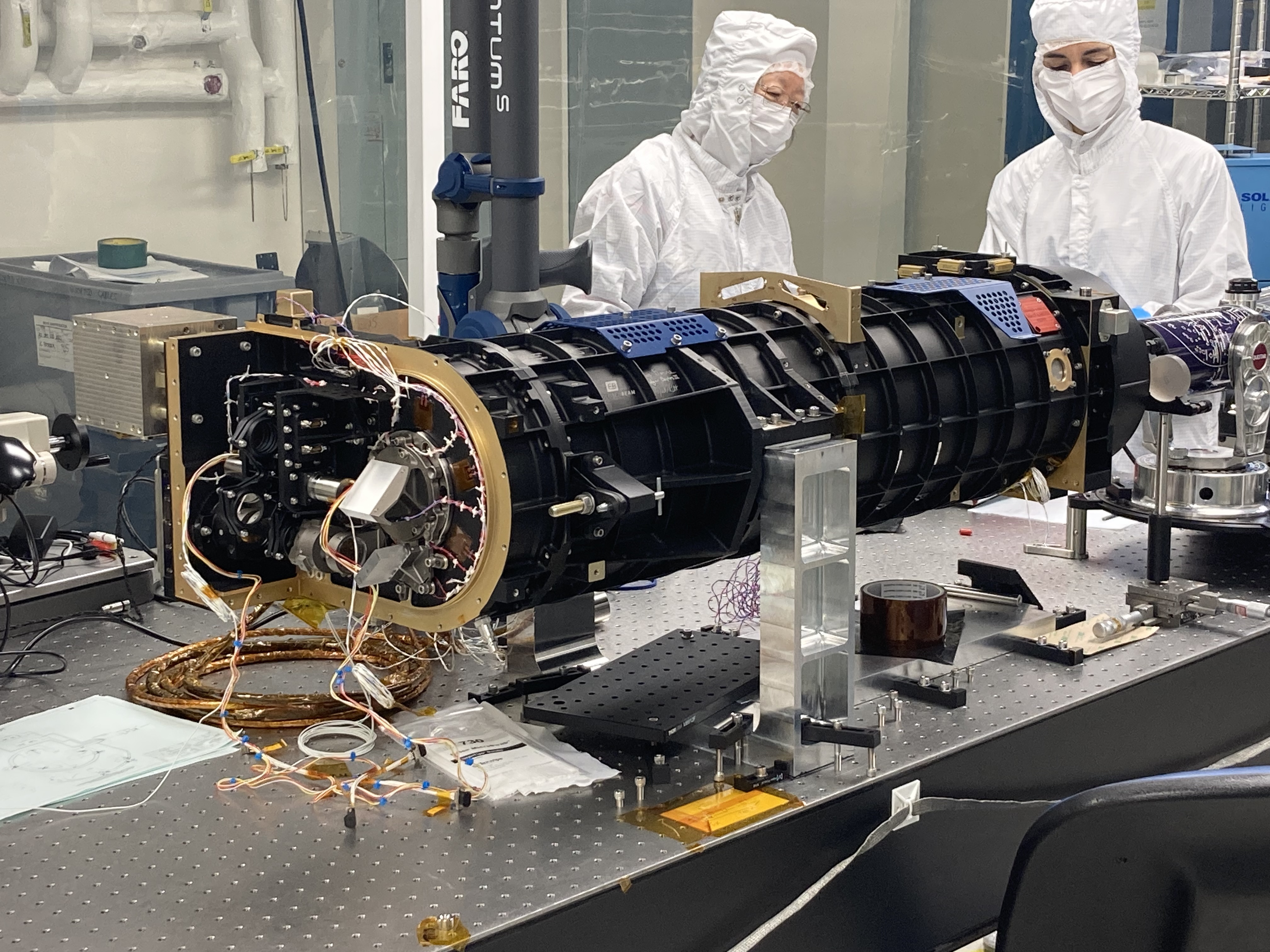

NASA to Launch Innovative Solar Coronagraph to Space Station

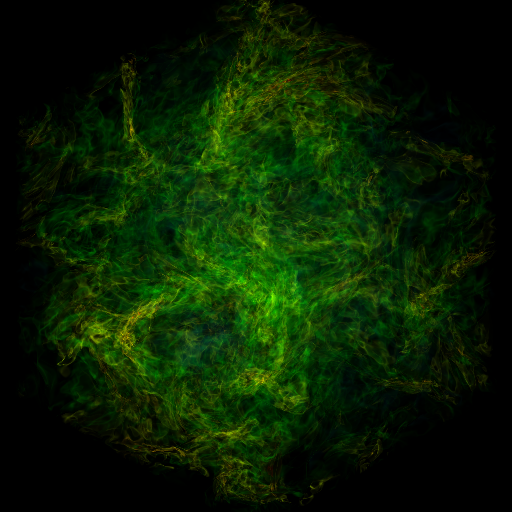

Buckle Up: NASA-Funded Study Explores Turbulence in Molecular Clouds

Hubble Sees a Celestial Cannonball

NASA Reveals Prototype Telescope for Gravitational Wave Observatory

GeneLab Chats with Gbolaga Olanrewaju on His Latest Publication

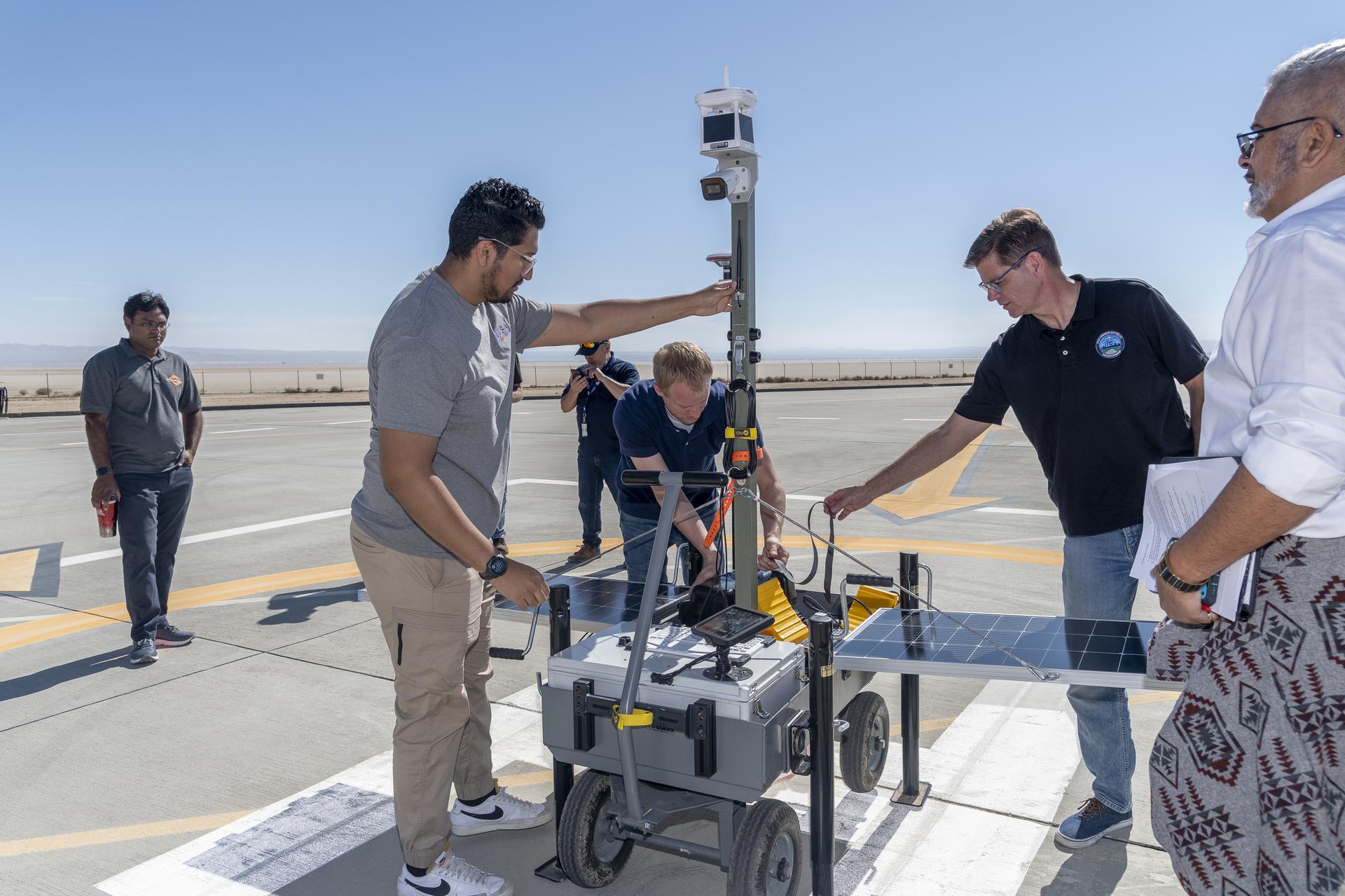

NASA and Partners Scaling to New Heights in Air Traffic Management

NASA Pilots Add Perspective to Research

NASA Spotlight: Felipe Valdez, an Inspiring Engineer

NASA Technologies Named Among TIME Inventions of 2024

After 60 Years, Nuclear Power for Spaceflight is Still Tried and True

2024 NASA Power to Explore Contest Winners

Journey Through Stars with NASA in New Minecraft Game

NASA-Themed Pumpkin-Carving Templates and Stencils

NASA Group Amplifies Voices of Employees with Disabilities

Autumn Leaves – Call for Volunteers

La NASA lleva un dron y un rover espacial a un espectáculo aéreo

Destacado de la nasa: felipe valdez, un ingeniero inspirador.

Sacrificio y Éxito: Ingeniero de la NASA honra sus orígenes familiares

5 hazards of human spaceflight.

Astronauts encounter five hazards as they journey through space. Recognizing these hazards allows NASA to seek ways that overcome the challenges of sending humans to the space station, the Moon, Mars, and beyond.

About the Five Hazards

A human journey to Mars, at first glance, offers an inexhaustible amount of complexities. To bring such a mission to the Red Planet from fiction to fact, NASA’s Human Research Program has pinpointed five hazards that astronauts will encounter on their journeys. These include space radiation , isolation and confinement , distance from Earth , gravity (and the lack of it), and closed or hostile environments. Scroll down to learn details involving each hazard.

Pooling the challenges of human spaceflight into categories allows for an organized effort to overcome the obstacles that lay before such a mission. However, these hazards do not stand alone. They can feed off one another and exacerbate effects on the human body, which are being studied using ground-based analogs , laboratories, and the International Space Station . These locations all serve as test beds to evaluate human performance, as well as the effectiveness of strategies that could keep astronauts safe and healthy in space.

Through meticulous research, NASA is gaining valuable insight into how the human body and mind might respond during extended forays into space. The resulting data, technology, and methods serve as a knowledge bank from which scientists can extrapolate to multi-year interplanetary missions.

Explore the five hazards of human spaceflight below:

Space Radiation

Invisible to the human eye, space radiation is not only stealthy but considered one of the most hazardous aspects of spaceflight.

Isolation and Confinement

Behavioral responses occur among groups of people far from Earth who are isolated and confined in a small space over a long period of time.

Distance from Earth

Instructions, new supplies, medical care, and more become increasingly challenging to receive from Earth as astronauts venture deeper into space.

Gravity Fields

Astronauts' entire bodies – muscles, bones, inner ear, and organs – must adjust to the new gravities encountered on the space station or their spacecraft, as well as on the Moon, Mars, and Earth once they return home.

Hostile/Closed Environments

Maintaining a safe ecosystem inside a spacecraft presents unique challenges, from ensuring optimal temperatures, pressures, and lighting, to reducing noise, monitoring microbial communities, and tracking immune responses.

Watch Videos

This hazard of a human mission to Mars is the most difficult to visualize because, well, space radiation is invisible to the human eye. Radiation is not only stealthy, but considered one of the most hazardous aspects of spaceflight.

Behavioral responses occur among groups of people isolated and confined in a small space over a long period of time. Crews must be carefully chosen, trained, and supported to ensure they can work effectively as a team for months or years in space.

Distance From Earth

Mars is, on average, 140 million miles from Earth. Rather than a three-day lunar trip, astronauts would be leaving our planet for roughly three years. Planning and self-sufficiency will be key to successful deep space missions.

On Mars, astronauts would need to live and work in three-eighths of Earth’s gravitational pull for up to two years. Throughout this time, their bodies – muscles, bones, inner ear, and organs – will be adjusting to new gravitational loads.

A spacecraft is not only a home, it’s also a machine. The ecosystem inside a vehicle plays a big role in everyday astronaut life. Important habitability factors include temperature, pressure, lighting, noise, the presence of microbes, and more.

Discover More Topics From NASA

Humans In Space

Space Station Research and Technology

NASA scientists consider the health risks of space travel

Humans aren't built to live in space, and being there can pose serious health risks . For space administrations like NASA, a major goal is to identify these risks to hopefully help lessen them.

That was a major theme during NASA’s Spaceflight for Everybody Virtual Symposium in November, a virtual symposium dedicated to discussing current knowledge and research efforts around the impact of spaceflight on human health. During a panel discussion titled “Human Health Risks in the Development of Future Programs” on Nov. 9, NASA scientists discussed these risks and how they are using existing knowledge to plan future missions.

Each panelist emphasized that the health risks presented by space travel are complex and multifaceted and that all types of risks should be considered closely when planning future missions.

Related: Space travel can seriously change your brain

- Spending time in space can harm the human body — but scientists are working to mitigate these risks before sending people to Mars

- Astronauts Will Face Many Hazards on a Journey to Mars

Five types of risk

When discussing the risks presented by living in space and space travel, there are five main types, the scientists outlined in the presentation.

Two types of risk, radiation and altered gravity, come simply from being in space, they said. Research has shown that both can have major negative effects on the body, and even the brain . Others, like isolation and confinement as well as being in a hostile closed environment, encompass risks posed by the living situations that are necessary in space, including risks to both mental and physical health.

Then, there are the risks presented simply by being a long way from Earth. The farther humans get from the Earth, the riskier living in space becomes in almost every way.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Everything from fresh food to unexpired medication will be extremely difficult to make accessible with longer journeys farther away. On the International Space Station, astronauts aren’t too far from us, and we can routinely send supplies to the crews in orbit. But a mission to the moon or Mars would pose more problems.

Communication delays would increase, and there would likely be communication blackouts, said Sharmi Watkins, assistant director for exploration in NASA’s Human Health and Performance Directorate who served as a panelist for this discussion. She said it would also take longer to get back to Earth if there was a medical emergency.

"We're not going to measure it in hours, but rather in days, in the case of the moon, and potentially weeks or months, when we start to think about Mars," said Watkins.

Steve Platts, the chief scientist in NASA’s human research program, broke down different levels of risk in space and discussed how NASA uses a "phased approach" when it comes to research on human health. In this approach, initial "phases" include research on the health effects of being in space has also been done in simulated conditions on Earth, from isolation experiments in Antarctica to radiation exposure at Brookhaven National Laboratory in Long Island, New York. Likewise, experiments on the space station will help us to prepare for risk on the moon and Mars — these later phases build on knowledge gained from simulations.

"We do work on Earth, we do work on low earth orbit and then we'll be doing lunar missions, all to help us get to Mars," Platts said.

— Deep-space radiation could cause have big impacts on the brain, mouse experiment shows

— Without gravity, the fluid around an astronaut's brain moves in weird ways

— Long space missions can change astronaut brain structure and function

Still, no matter how much we may prepare on Earth, every space mission comes with risk, so NASA has set health standards to minimize this risk for astronauts.

NASA has over 800 health standards that they’ve developed based on current research. These standards describe everything from how much space astronauts should have in a spacecraft to how much muscle and bone loss an astronaut can experience without being seriously harmed. These standards also include levels of physical fitness and health the astronauts need to meet before going into space. All of NASA’s health standards for astronauts are available online .

A mission can impact astronauts’ health, but it also works the other way — health troubles with astronauts could impact a mission if they aren’t able to perform mission tasks adequately, said Mary Van Baalen, acting director of human system risk management at NASA and the panel’s moderator. She emphasized the complex interplay between these two types of impacts, both of which NASA scientists must keep in mind when planning missions.

"Space travel is an inherently risky endeavor," she said. "And the nature of human risk is complex."

You can watch the full recording of the panel discussion and other talks from the symposium here .

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: [email protected].

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: [email protected].

Rebecca Sohn is a freelance science writer. She writes about a variety of science, health and environmental topics, and is particularly interested in how science impacts people's lives. She has been an intern at CalMatters and STAT, as well as a science fellow at Mashable. Rebecca, a native of the Boston area, studied English literature and minored in music at Skidmore College in Upstate New York and later studied science journalism at New York University.

Apollo 11 moonwalker Buzz Aldrin endorses Trump for president

SpaceX launches 23 Starlink satellites from Florida (video, photos)

Can 'failed stars' have planets? James Webb Space Telescopes offers clues

Most Popular

- 2 NASA astronaut snaps spooky photo of SpaceX Dragon capsule from ISS

- 3 Apollo 11 moonwalker Buzz Aldrin endorses Trump for president

- 4 Astrophotographer captures comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS growing an anti-tail (photos)

- 5 SpaceX launches 23 Starlink satellites from Florida (video, photos)

The many, many reasons space travel is bad for the human body

Leaving earth upends almost every system inside of us.

After the astronaut Scott Kelly spent a year on the International Space Station, he returned to Earth shorter, more nearsighted, lighter and with new symptoms of heart disease that his identical twin brother did not share. (Mark Kelly, now a U.S. senator, also spent a brief time in space.)

Even their DNA diverged, as nearly 1,000 of Scott Kelly’s genes and chromosomes worked differently. (On the upside, he aged about 9 milliseconds less that year, thanks to how fast the space station circled the Earth.)

Most of these effects cleared up within a few months, but not all — underscoring the potential health hazards of space travel, many of which are unknown. These will ratchet up during ambitious future trips, such as NASA’s planned Artemis mission to the moon and later travel to Mars.

Even a partial list of the likely physical and emotional consequences of deep space travel is daunting.

Your browser does not support the video element.

Space motion sickness sets in almost immediately. The nausea, dizziness, headaches and confusion can linger for days.

“Puffy Face Bird Leg Phenomenon” develops, as blood and other bodily fluids rush to the upper body in low gravity and stay there, swelling heads and shrinking legs.

Astronauts’ appearances can change as their faces swell. The astronauts may feel congested, as though they have a constant head cold.

Muscles atrophy by as much as 1 percent every week in weightlessness, especially in the legs.

Blood volume drops — and with less blood to pump, the heart weakens and loses its signature heart shape, growing more rounded.

Like any other muscle, the heart doesn’t need to work as hard in microgravity and will begin to atrophy without rigorous exercise.

Doused with radiation, many immune cells die and immunity is lowered. There’s also DNA damage, potentially upping cancer risk.

Inflammation spikes throughout the body, possibly contributing to heart disease and other conditions.

Bones thin by about 1.5 percent a month. Spinal discs harden.

In the head, parts of the eyeball can flatten, causing sharper distance vision and dimmer near vision.

Fluids flood the skull, diminishing smell and hearing.

Gene activity changes, including in the brain. In mice, 54 different genes in the brain worked differently after weeks in space.

Brain cells can be affected by radiation, diminishing memory and thinking (in mice).

Circadian rhythms falter, making insomnia common.

Finally, months or years of solitude — or close confinement with fellow astronauts — can lead to lasting psychological stress.

“Space is just not very hospitable to the human body,” said Emmanuel Urquieta, chief medical officer at the Translational Research Institute for Space Health in Houston, which partners with NASA to study the effects of deep space exploration.

Humans evolved in conditions of plentiful gravity and relatively slight background radiation, he said. Space is the reverse and it upends the operations of almost every biological system inside of us. —

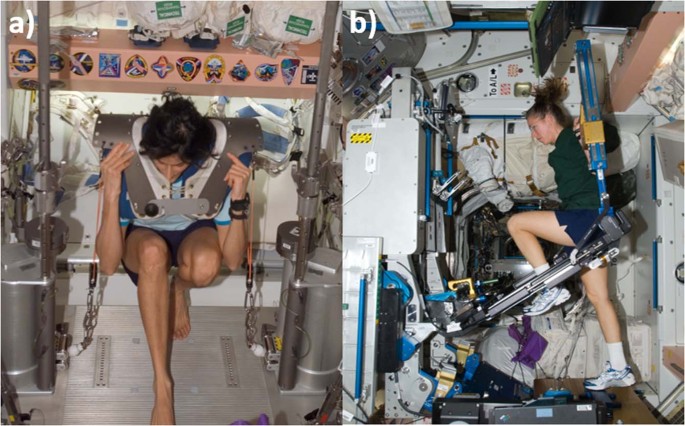

Most of the potential health risks of space travel can be mitigated to some extent, scientists point out. Exercise, for instance, “is quite effective” at helping astronauts maintain muscle mass and bone density, said Lori Ploutz-Snyder, the dean of the University of Michigan School of Kinesiology. She was previously a researcher at NASA, where she led studies of exercise and space travel.

The New Space Age

On the space station, astronauts routinely work out for about an hour most days, she said, using specialized devices to run, cycle and lift weights, despite being weightless. But on lunar and Mars missions, which will involve smaller ships and possibly years-long durations, exercise equipment will need to be shrunk and astronauts’ willingness to keep up with the workouts enlarged.

[ To counter the effect of sitting too much, try the astronaut workout ]

The Earth’s magnetic field shields the relatively close-in space station as well from some of the worst deep-space radiation, but the lunar and Mars missions — higher and farther from Earth — will not enjoy that protection.

The moon and Mars journeys will demand advanced shielding, Urquieta said, together with drugs and supplements that might lessen some of the internal effects of the remaining — and inevitable — radiation. Antioxidants, such as vitamins C and E, could sop up a portion of the damaging molecules released after radiation exposure, while other protective drugs and nutrients are under investigation, he said.

Despite every available precaution and protection, deep space will remain a harsh, unwelcoming place for the human body. But it will also, and always, represent something else for the human imagination, Urquieta said — its endless sweep of sequined darkness sparking our ambitions, dreams and stories.

Which is why, even knowing better than most people the toll such a trip might take on him, he would go into space “in a heartbeat,” he said. “Absolutely. No question. It’s so inspiring. It’s space."

About this story

Additional design and development by Betty Chavarria. Editing by Kate Rabinowitz, Manuel Canales and Jeff Dooley. Copy editing by Wayne Lockwood.

Scientists Release Largest Trove of Data on How Space Travel Affects the Human Body

A collection of 44 new studies, largely based on a short-duration tourist trip in 2021, provides insight into the health effects of traveling to space

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Will-Sullivan-photo.png)

Will Sullivan

Daily Correspondent

:focal(960x549:961x550)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b6/ca/b6cada46-c092-4fe2-8c88-d4b30b9841d4/51548866865_0802a42ef8_o.jpg)

More and more humans are traveling to space. Several missions in 2021 took private citizens on tourist flights. Last month, six people flew to the edge of Earth’s atmosphere and back. NASA plans to put astronauts back on the moon later this decade, and SpaceX recently tested a rocket it hopes will one day carry humans to Mars.

With even more ambitious crewed flights on the horizon, scientists want to better understand the effects that space’s stressors—such as exposure to radiation and a lack of gravity—have on the human body. Now, a newly released set of 44 papers and troves of data, called the Space Omics and Medical Atlas (SOMA), aims to do just that.

SOMA is the largest collection of data on aerospace medicine and space biology ever compiled. It dramatically expands the amount of information available on how the human body changes during spaceflight. And the first studies to come out of this project improve scientists’ understanding of how space travel affects human health.

“This will allow us to be better prepared when we’re sending humans into space for whatever reason,” Allen Liu , mechanical engineer at the University of Michigan who is not involved in the project, tells Adithi Ramakrishnan of the Associated Press (AP).

Much of the new atlas is based on data collected from the four members of the Inspiration4 mission , a space tourism flight that sent four civilians on a three-day trip to low-Earth orbit in September 2021. The findings suggest people on short-term flights experience some of the same health impacts that astronauts face on long-term trips to space.

“We don’t yet fully understand all of the risks” of long-duration space travel, Amy McGuire , a biomedical ethicist at Baylor College of Medicine who did not contribute to the work, says to Science ’s Ramin Skibba. “This is also why it is so important that early space tourists participate in research.”

Space travel poses a number of risks to health. Without Earth’s atmosphere and magnetic field to protect them, astronauts are exposed to space radiation , which can increase their risk for cancer and degenerative diseases. Fluid shifts into astronauts’ heads when they are experiencing weightlessness, which can contribute to vision problems , headaches and changes in the structure of the brain . The microgravity environment can also lead to a loss of bone density and atrophied muscles , prompting long-haul astronauts to adopt specific exercise regimens .

But on top of those known risks, the new research highlights other potential issues. One study published Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications found that mice exposed to a dose of radiation meant to simulate a round trip to Mars experienced kidney damage and dysfunction. Human travelers might need to be on dialysis on the way back from the Red Planet if they were not protected from this radiation, writes the Guardian ’s Ian Sample.

“It’s likely to be a serious issue,” Stephen Walsh , a co-author of the study and clinician scientist at University College London, tells the publication. “It’s very hard to see how that’s going to be okay.”

The health information from the Inspiration4 astronauts sheds light on how space travel can affect private citizens who have not extensively trained for it. The findings also highlight changes to cells and DNA that can occur during short trips to space.

Biomarkers that changed during the Inspiration4 mission returned to normal a few months after the trip, suggesting that space travel doesn’t pose a greater risk to civilians than it does for trained astronauts, Christopher Mason , a geneticist at Cornell University who helped put together the atlas, says to New Scientist ’s Clare Wilson.

The Inspiration4 research also suggests women may recover faster from space travel than men. Data from the mission’s two male and two female participants, along with data from 64 NASA astronauts, indicated that gene activity related to the immune system was more disrupted in male astronauts, per the Guardian . And men’s immune systems took longer to return to normal once back on Earth.

Taken together, the new papers could help researchers learn how to ameliorate the harms space travel can cause, Afshin Beheshti , a co-author of the work and a researcher with the Blue Marble Space Institute of Science, says to the AP.

And the scientists say nothing in the data suggests humans should not go to space.

“There’s no showstopper,” Mason tells the Washington Post ’s Joel Achenbach. “There’s no reason we shouldn’t be able to safely get to Mars and back.”

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Will-Sullivan-photo.png)

Will Sullivan | | READ MORE

Will Sullivan is a science writer based in Washington, D.C. His work has appeared in Inside Science and NOVA Next .

Spending time in space can harm the human body − but scientists are working to mitigate these risks before sending people to Mars

Professor of Applied Physiology & Kinesiology, University of Florida

Disclosure statement

Rachael Seidler receives funding from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the Translational Research Institue for Space Health, the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and the Office of Naval Research.

University of Florida provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation US.

View all partners

When 17 people were in orbit around the Earth all at the same time on May 30, 2023, it set a record. With NASA and other federal space agencies planning more manned missions and commercial companies bringing people to space, opportunities for human space travel are rapidly expanding.

However, traveling to space poses risks to the human body. Since NASA wants to send a manned mission to Mars in the 2030s, scientists need to find solutions for these hazards sooner rather than later.

As a kinesiologist who works with astronauts, I’ve spent years studying the effects space can have on the body and brain. I’m also involved in a NASA project that aims to mitigate the health hazards that participants of a future mission to Mars might face.

Space radiation

The Earth has a protective shield called a magnetosphere , which is the area of space around a planet that is controlled by its magnetic field . This shield filters out cosmic radiation . However, astronauts traveling farther than the International Space Station will face continuous exposure to this radiation – equivalent to between 150 and 6,000 chest X-rays .

This radiation can harm the nervous and cardiovascular systems including heart and arteries , leading to cardiovascular disease. In addition, it can make the blood-brain barrier leak . This can expose the brain to chemicals and proteins that are harmful to it – compounds that are safe in the blood but toxic to the brain.

NASA is developing technology that can shield travelers on a Mars mission from radiation by building deflecting materials such as Kevlar and polyethylene into space vehicles and spacesuits . Certain diets and supplements such as enterade may also minimize the effects of radiation. Supplements like this, also used in cancer patients on Earth during radiation therapy, can alleviate gastrointestinal side effects of radiation exposure.

Gravitational changes

Astronauts have to exercise in space to minimize the muscle loss they’ll face after a long mission. Missions that go as far as Mars will have to make sure astronauts have supplements such as bisphosphonate , which is used to prevent bone breakdown in osteoporosis. These supplements should keep their muscles and bones in good condition over long periods of time spent without the effects of Earth’s gravity .

Microgravity also affects the nervous and circulatory systems. On Earth, your heart pumps blood upward, and specialized valves in your circulatory system keep bodily fluids from pooling at your feet. In the absence of gravity, fluids shift toward the head.

My work and that of others has shown that this results in an expansion of fluid-filled spaces in the middle of the brain. Having extra fluid in the skull and no gravity to “hold the brain down” causes the brain to sit higher in the skull , compressing the top of the brain against the inside of the skull.

These fluid shifts may contribute to spaceflight associated neuro-ocular syndrome , a condition experienced by many astronauts that affects the structure and function of the eyes . The back of the eye can become flattened, and the nerves that carry visual information from the eye to the brain swell and bend. Astronauts can still see, though visual function may worsen for some. Though it hasn’t been well studied yet, case studies suggest this condition may persist even a few years after returning to Earth.

Scientists may be able to shift the fluids back toward the lower body using specialized “pants ” that pull fluids back down toward the lower body like a vacuum. These pants could be used to redistribute the body’s fluids in a way that is more similar to what occurs on Earth.

Mental health and isolation

While space travel can damage the body, the isolating nature of space travel can also have profound effects on the mind .

Imagine having to live and work with the same small group of people, without being able to see your family or friends for months on end. To learn to manage extreme environments and maintain communication and leadership dynamics, astronauts first undergo team training on Earth.

They spend weeks in either NASA’s Extreme Environment Mission Operations at the Aquarius Research Station , found underwater off the Florida Keys, or mapping and exploring caves with the European Space Agency’s CAVES program . These programs help astronauts build camaraderie with their teammates and learn how to manage stress and loneliness in a hostile, faraway environment.

Researchers are studying how to best monitor and support behavioral mental health under these extreme and isolating conditions.

While space travel comes with stressors and the potential for loneliness, astronauts describe experiencing an overview effect : a sense of awe and connectedness with all humankind. This often happens when viewing Earth from the International Space Station.

Learning how to support human health and physiology in space also has numerous benefits for life on Earth . For example, products that shield astronauts from space radiation and counter its harmful effects on our body can also treat cancer patients receiving radiation treatments.

Understanding how to protect our bones and muscles in microgravity could improve how doctors treat the frailty that often accompanies aging. And space exploration has led to many technological achievements advancing water purification and satellite systems .

Researchers like me who study ways to preserve astronaut health expect our work will benefit people both in space and here at home.

- Magnetosphere

- Cardiovascular health

- European Space Agency (ESA)

- Nervous system

- Artemis program

- International Space Station

- blood-brain barrier

Commissioning Editor Nigeria

Subject Coordinator PCP2

Professor in Physiotherapy

Postdoctoral Research Associate

Editorial Internship

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 05 November 2020

Red risks for a journey to the red planet: The highest priority human health risks for a mission to Mars

- Zarana S. Patel ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0996-6381 1 , 2 ,

- Tyson J. Brunstetter 3 ,

- William J. Tarver 2 ,

- Alexandra M. Whitmire 2 ,

- Sara R. Zwart 2 , 4 ,

- Scott M. Smith 2 &

- Janice L. Huff ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4236-7698 5

npj Microgravity volume 6 , Article number: 33 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

98k Accesses

373 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Cardiovascular diseases

- Eye diseases

- Neurological disorders

- Psychiatric disorders

NASA’s plans for space exploration include a return to the Moon to stay—boots back on the lunar surface with an orbital outpost. This station will be a launch point for voyages to destinations further away in our solar system, including journeys to the red planet Mars. To ensure success of these missions, health and performance risks associated with the unique hazards of spaceflight must be adequately controlled. These hazards—space radiation, altered gravity fields, isolation and confinement, closed environments, and distance from Earth—are linked with over 30 human health risks as documented by NASA’s Human Research Program. The programmatic goal is to develop the tools and technologies to adequately mitigate, control, or accept these risks. The risks ranked as “red” have the highest priority based on both the likelihood of occurrence and the severity of their impact on human health, performance in mission, and long-term quality of life. These include: (1) space radiation health effects of cancer, cardiovascular disease, and cognitive decrements (2) Spaceflight-Associated Neuro-ocular Syndrome (3) behavioral health and performance decrements, and (4) inadequate food and nutrition. Evaluation of the hazards and risks in terms of the space exposome—the total sum of spaceflight and lifetime exposures and how they relate to genetics and determine the whole-body outcome—will provide a comprehensive picture of risk profiles for individual astronauts. In this review, we provide a primer on these “red” risks for the research community. The aim is to inform the development of studies and projects with high potential for generating both new knowledge and technologies to assist with mitigating multisystem risks to crew health during exploratory missions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Selected discoveries from human research in space that are relevant to human health on Earth

Molecular and physiological changes in the SpaceX Inspiration4 civilian crew

Impact of diet on human nutrition, immune response, gut microbiome, and cognition in an isolated and confined mission environment

Introduction.

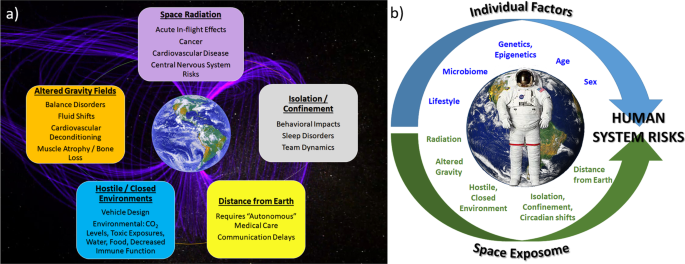

Spaceflight is a dangerous and demanding endeavor with unique hazards and technical challenges. Ensuring the overall safety of the crew—their physical and mental health and well-being—are vital for mission success. These are large challenges that are further amplified as exploration campaigns extend to greater distances into our solar system and for longer durations. The major health hazards of spaceflight include higher levels of damaging radiation, altered gravity fields, long periods of isolation and confinement, a closed and potentially hostile living environment, and the stress associated with being a long distance from mother Earth. Each of these threats is associated with its own set of physiological and performance risks to the crew (Fig. 1a ) that must be adequately characterized and sufficiently mitigated. Crews do not experience these stressors independently, so it is important to also consider their combined impact on human physiology and performance. This “space exposome” is a unifying framework that reflects the interaction of all the environmental impacts on the human body (Fig. 1b ) and, when combined with individual genetics, will shape the outcomes of space travel on the human system 1 , 2 .

a The key threats to human health and performance associated with spaceflight are radiation, altered gravity fields, hostile and closed environments, distance from Earth, and isolation and confinement. From these five hazards stem the health and performance risks studied by NASA’s Human Research Program. b The space exposome considers the summation of an individual’s environmental exposures and their interaction with individual factors such as age, sex, genomics, etc. - these interactions are ultimately responsible for risks to the human system. Images used in this figure are courtesy of NASA.

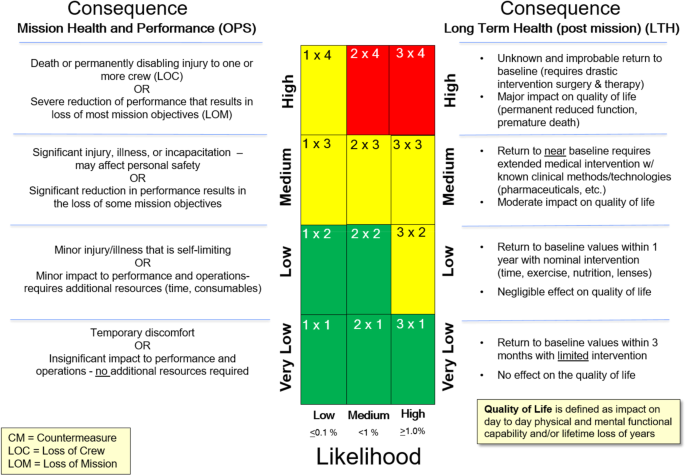

The NASA Human Research Program (HRP) aims to develop and provide the knowledge base, technologies, and countermeasure strategies that will permit safe and successful human spaceflight. With agency resources and planning directed toward extended missions both within low Earth orbit (LEO) and outside LEO (including cis-lunar space, lunar surface operations, a lunar outpost, and exploration of Mars) 3 , HRP research and development efforts are focused on mitigation of over 30 categories of health risks relevant to these missions. The HRP’s current research strategy, portfolio, and evidence base are described in the HRP Integrated Research Plan (IRP) and are available online in the Human Research Roadmap, a managed tool used to convey these plans ( https://humanresearchroadmap.nasa.gov/ ). To determine research priorities, NASA uses an evidence-based risk approach to assess the likelihood and consequence (LxC), which gauges the level of each risk for a set of standard design reference missions (Fig. 2 ) 4 . Risks are assigned a rating for their potential to impact in-mission crew health and performance and for their potential to impact long-term health outcomes and quality of life. “Red” risks are those that are considered the highest priority due to their greatest likelihood of occurrence and their association with the most significant risks to crew health and performance for a given design reference mission (DRM). Risks rated “yellow” are considered medium level risks and are either accepted due to a very low probability of occurrence, require in-mission monitoring to be accepted, or require refinement of standards or mitigation strategies in order to be accepted. Risks rated “green” are considered sufficiently controlled either due to lower likelihood and consequence or because the current knowledge base provides sufficient mitigation strategies to control the risk to an acceptable level for that DRM. Milestones and planned program deliverables intended to move a risk rating to an acceptable, controlled level are detailed in a format known as the path to risk reduction (PRR) and are developed for each of the identified risks. The most recent IRP and PRR documents are useful resources for investigators during the development of relevant research approaches and proposals intended for submission to NASA HRP research announcements ( https://humanresearchroadmap.nasa.gov/Documents/IRP_Rev-Current.pdf ).

NASA uses an evidence-based approach to assess likelihood and consequence for each documented human system risk. The matrix used for classifying and prioritizing human system risks has two sets of consequences—the left side shows consequences for in-mission risks while the right side is used to evaluate long-term health consequences (Romero and Francisco) 4 .

This work reviews HRP-defined high priority “red” risks for crew health on exploration missions: (1) space radiation health effects that include cancer, cardiovascular disease, and cognitive decrements (2) Spaceflight-Associated Neuro-ocular Syndrome (3) behavioral health and performance decrements, and (4) inadequate food and nutrition. The approaches used to address these risks are described with the aim of informing potential NASA proposers on the challenges and high priority risks to crew health and performance present in the spaceflight environment. This should serve as a primer to help individual proposers develop projects with high potential for generating both new knowledge and technology to assist with mitigating risks to crew health during exploratory missions.

Space radiation health risks

Outside of the Earth’s protective magnetosphere, crews are exposed to pervasive, low dose-rate galactic cosmic rays (GCR) and to intermittent solar particle events (SPEs) 5 . Exposures from GCR are from high charge (Z) and energy (HZE) ions, high-energy protons, and secondary protons, neutrons, and fragments produced by interactions with spacecraft shielding and human tissues. The main components of an SPE are low-to-medium energy protons. In LEO, the exposures are from GCR modulated by the Earth’s magnetic field and from trapped protons in the South Atlantic Anomaly. The absorbed doses for crews on the International Space Station (ISS) on 6- to 12-month missions range from ~30 to 120 mGy. Outside of LEO, without the protection offered by the Earth’s magnetosphere, absorbed radiation doses will be significantly higher. Estimates for a 1 year stay on the lunar surface range from 100 to 120 mGy, and 300 to 450 mGy for an ~3-year Mars mission (transit and surface stay) 6 . The exact dose a crewmember will receive is highly dependent on exact parameters of a given mission, such as detailed vehicle and habitat designs, and mission location and duration 7 . Time in the solar cycle is also a large factor contributing to crew exposure, with highest GCR exposure occurring during periods of minimum solar activity. The lowest GCR exposures occur during periods of maximum solar activity when the heightened magnetic activity of the Sun diverts some cosmic rays; however, during maximum solar activity, the probability of an SPE is higher 8 , 9 . SPEs, which vary in the magnitude and frequency, will obviously also contribute to total mission doses so it is important to note that total mission exposures are only estimates. Further information on the space radiation environment that astronauts will experience is discussed in Simonsen et al. 5 and Durante and Cucinotta 10 .

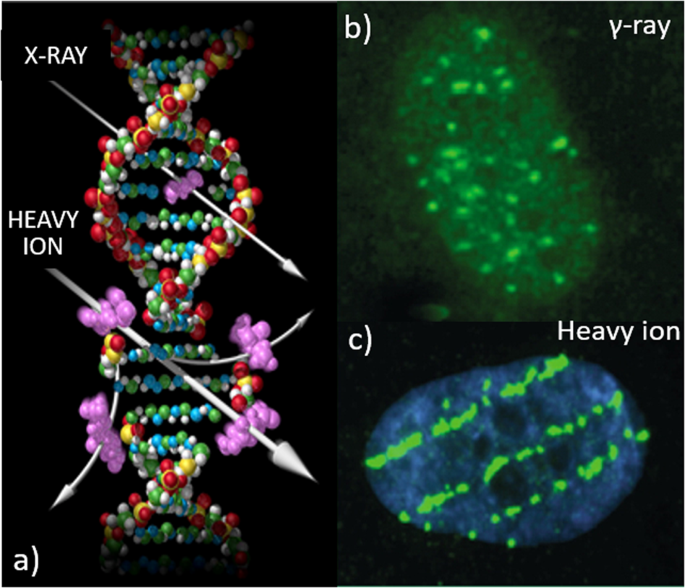

An important consideration for risk assessment is that the types of radiation encountered in space are very different from the types of radiation exposure we are familiar with here on Earth. HZE ions, although a small fraction of the overall GCR spectrum compared to protons, are more biologically damaging. They differ from terrestrial forms of radiation, such as X-rays and gamma-rays, in both the amount (dose) of exposure as well as in the patterns of DNA double-strand breaks and oxidative damage that they impart as they traverse through tissue and cells (Fig. 3 ) 5 . The highly energetic HZE particles produce complex DNA lesions with clustered double-stranded and single-stranded DNA breaks that are difficult to repair. This damage leads to distinct cellular behavior and intracellular signaling patterns that may be associated with altered disease outcomes compared to those for terrestrial sources of radiation 11 , 12 , 13 . As an example, persistently high levels of oxidative damage are observed in the intestine from mice examined 1 year after exposure to 56 Fe-ion radiation compared to gamma radiation and unirradiated controls 14 , 15 . The higher levels of residual oxidative damage in HZE ion-irradiated tissue is significant because of the association of oxidative stress and damage with the etiology of many human diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular and late neurodegenerative disorders. These types of alterations are believed to contribute to the higher biological effectiveness of HZE particles 10 , 11 .

a HZE ions produce dense ionization along the particle track as they traverse a tissue and impart distinct patterns of DNA damage compared to terrestrial radiation such as X-rays. γH2AX foci (green) illuminate distinct patterns of DNA double-strand breaks in nuclei of human fibroblast cells after exposure to b gamma-rays, with diffuse damage, and c HZE ions with single tracks. Image credits: NASA ( a ) and Cucinotta and Durante 97 ( b and c ).

Within the HRP, the Space Radiation Element (SRE) has developed a research strategy involving both vertical translation and horizontal integration, as well as products focused on mitigating space radiation risks across all phases of a mission. Vertical translation involves the integration of benchtop research with preclinical studies and clinical data. Horizontal integration involves a multidisciplinary approach that includes a range of expertize from physicians to clinicians, epidemiologists to computational modelers 16 . The suite of tools includes computational models of the space radiation environment, mission design tools, models for risk projection, and tools and technologies for accurate simulation of the space radiation environment for radiobiology investigations. Ongoing research is focused on radiation quality, age, sex, and healthy worker effects, medical countermeasures to reduce or eliminate space radiation health risks, understanding the complex nature of individual sensitivity, identification and validation of biomarkers (translational, surrogate, predictive, etc.) and integration of personalized risk assessment and mitigation approaches. Owing to the lack of human data for heavy ion exposure on Earth and the complications of obtaining reliable data for space radiation health effects from flight studies, SRE conducts research at the NASA Space Radiation Laboratory (NSRL) at Brookhaven National Laboratory. The NSRL is a ground-based analog for space radiation, where a beamline and associated experimental facilities are dedicated to the radiobiology and physics of a range of ions from proton and helium ions to the typical GCR ions such as carbon, silicon, titanium, oxygen, and iron 5 , 17 , 18 .

Radiation carcinogenesis

Central evidence for association between radiation exposure and the development of cancer and other non-cancer health effects comes from epidemiological studies of humans exposed to radiation 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 . Scaling factors are used by NASA and other space agencies in the analysis of cancer (and other risks) to account for differences between terrestrial radiation exposures and cosmic radiation exposures 23 . The risk of radiation carcinogenesis is considered a “red” risk for exploration-class missions due to both the high likelihood of occurrence, as well as the high potential for detrimental impact on both quality of life and disease-free survival post flight. The major cancers of concern are epithelial in origin (particularly cancers of the lung, breast, stomach, colon, and bladder), as well as leukemias ( https://humanresearchroadmap.nasa.gov/Evidence/reports/Cancer.pdf ). Owing to the lack of human epidemiology directly relevant to the types of radiation found in space, current research utilizes a translational approach that incorporates rodent and advanced human cell-based model systems exposed to space radiation simulants along with comparison of molecular pathways across these systems to the human.

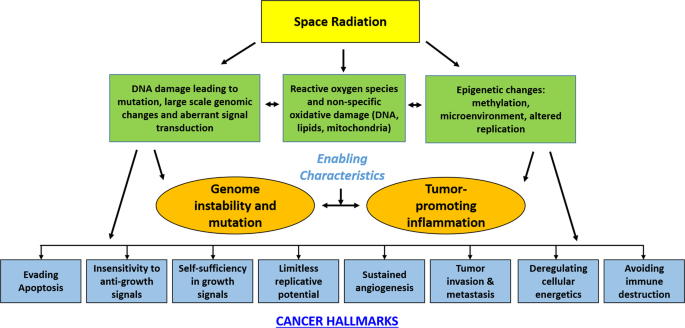

A key question that impacts risk assessment and mitigation is how HZE tumors compare to either radiogenic tumors induced by ground-based radiation or spontaneous tumors. As a unifying concept, NASA studies have sought to examine how space radiation exposure modifies the key genetic and epigenetic modifications noted as the hallmarks of cancer (Fig. 4 ) 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 . This approach provides data for development of translational scaling factors (relative biological effectiveness values, quality factors, dose-rate effectiveness factor) to relate the biological effects of space radiation to effects from similar exposures to ground-based gamma- and X-rays and extrapolation of results to large human epidemiology cohorts. It also supports acquisition of mechanistic information required for successful identification and implementation of medical countermeasure strategies to lower this risk to an acceptable posture for space exploration, and it is relevant for the future development of biologically based dose-response models and integrated systems biology approaches 25 . Cancer is a long-term health risk and although it is rated as “red”, most research in this area is currently delayed, as HRP research priorities focus on in-mission risks.

Shown are the enabling characteristics and possible mechanisms of radiation damage that lead to these changes observed in all human tumors. (Adapted from Hanahanand Weinberg) 24 .

Risk of cardiovascular disease and other degenerative tissue effects from radiation exposure and secondary spaceflight stressors

A large number of degenerative tissue (non-cancer) adverse health outcomes are associated with terrestrial radiation exposure, including cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, cataracts, digestive and endocrine disorders, immune system decrements, and respiratory dysfunction ( https://humanresearchroadmap.nasa.gov/Evidence/other/Degen.pdf ). For cardiovascular disease (CVD), a majority of the evidence comes from radiotherapy cohorts receiving high-dose mediastinal exposures that are associated with an increased risk for heart attack and stroke 28 . Recent evidence shows risk at lower doses (<0.5 Gy), with an estimated latency of 10 years or more 29 , 30 , 31 . For a Mars mission, preliminary estimates suggest that circulatory disease risk may increase the risk of exposure induced death by ~40% compared to cancer alone 32 . NASA is also concerned about in-flight risks to the cardiovascular system ( https://humanresearchroadmap.nasa.gov/Evidence/other/Arrhythmia.pdf ), when considering the combined effects of radiation exposure and other spaceflight hazards (Fig. 5 ) 33 . The Space Radiation Element is focused on accumulating data specific to the space radiation environment to characterize and quantify the magnitude of the degenerative disease risks. The current efforts are on establishing dose thresholds, understanding the impact of dose-rate and radiation quality effects, uncovering mechanisms and pathways of radiation-associated cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, and subsequent risk modeling for astronauts. Uncovering the mechanistic underpinnings governing disease processes supports the development of specific diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, is a necessary step in the translation of insights from animal models to humans, and is the basis of personalized medicine approaches.

In blue are the known risk factors for CVD and in black are the other spaceflight stressors that may also contribute to disease development. Image used in this figure is courtesy of NASA.

This information will provide a means to reduce the uncertainty in current permissible exposure limits (PELs), quantify the impact to disease-free survival years, and determine if additional protection or mitigation strategies are required. The research portfolio includes evaluation of current clinical standard-of-care biomarkers for their relevance as surrogate endpoints for radiation-induced disease outcomes. Studies are also addressing the possible role of chronic inflammation and increased oxidative stress in the etiology of radiation-induced CVD, as well as identification of key events in disease pathways, like endothelial dysfunction, that will guide the most effective medical countermeasures. Products include validated space radiation PELs, models to quantify the risk of CVD for the astronaut cohort, and countermeasures and evidence to inform development of appropriate recommendations to clinical guidelines for diagnosis and mitigation of this risk.

Elucidating the role that radiation plays in degenerative disease risks is problematic because multiple factors, including lifestyle and genetic influences, are believed to play a major role in the etiology of these diseases. This confounds epidemiological analyses, making it difficult to detect significant differences from background disease without a large study population 34 . This issue is especially significant in astronaut cohorts because those studies have small sample sizes 35 . There is also a general lack of experimental data that specifically addresses the role of radiation at low, space-relevant doses 36 . Selection of experimental models needs to be carefully considered and planned to ensure that the cardiovascular disease mechanisms and study endpoints are clinically relevant and translatable to humans 37 , 38 . Combined approaches using data from wildtype and genetically modified animal models with accelerated disease development will likely be necessary to elucidate mechanisms and generate the body of knowledge required for development of accurate permissible exposure limits, risk assessment models, and to develop effective mitigation approaches.

Risk of acute (in-flight) and late CNS effects from space radiation exposure

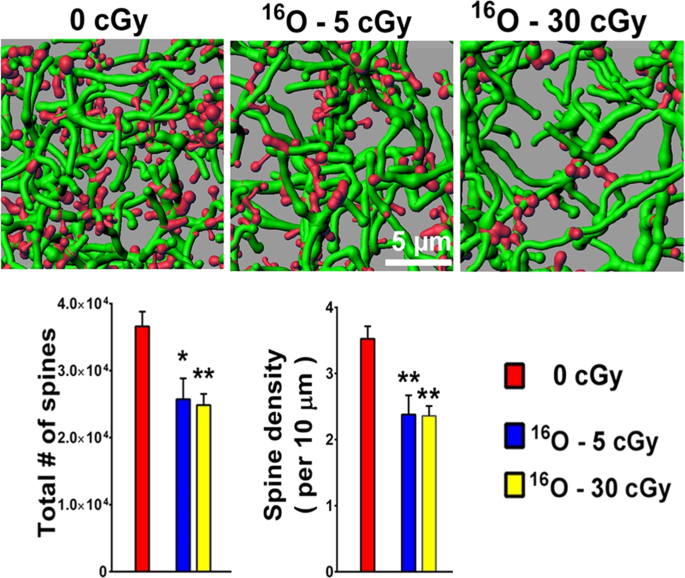

The possibility of acute (in-flight) and late risks to the central nervous system (CNS) from GCR and SPEs are concerns for human exploration of space ( https://humanresearchroadmap.nasa.gov/Evidence/reports/CNS.pdf ). Acute CNS risks may include altered neurocognitive function, impaired motor function, and neurobehavioral changes, all of which may affect human health and performance during a mission. Late CNS risks may include neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, or accelerated aging. Detrimental CNS changes from radiation exposure are observed in humans treated with high doses of gamma-rays or proton beams and are supported by a large body of experimental evidence showing neurocognitive and behavioral effects in animal models exposed to lower doses of HZE ions. Rodent studies conducted with HZE ions at low, mission-relevant doses and time frames show a variety of structural and functional alterations to neurons and neural circuits with associated performance deficits 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 . Fig. 6 shows an example of changes in dendritic spine density following HZE ion radiation. However, the significance and relationship of these results to adverse outcomes in astronauts is unclear, as similar decrements are not seen with comparable doses of terrestrial radiation. Therefore, scaling to human epidemiology data, as is done for cancer and cardiovascular disease, is not possible. It is also important to note that to date, no radiation-associated clinically significant operational or long-term deficits have been identified in astronauts receiving similar doses via long-duration ISS missions. It is clear that further development of standardized translational models, research paradigms, and appropriate scaling approaches are required to determine significance in humans 45 , 46 . In addition, elucidation of how space radiation interacts with other mission hazards to impact neurocognitive and behavioral health and performance is critical to defining appropriate PELs and countermeasure strategies. The current research approach is a combined effort of SRE, the human factors and behavioral performance element, and the human health countermeasures element in support of an integrated CBS (CNS/behavioral medicine/sensorimotor) plan ( https://humanresearchroadmap.nasa.gov/Risks/risk.aspx?i=99 ). Further information on this risk area is presented below in the Behavioral Health and Performance section and can also be found at the Human Research Roadmap.

Representative digital images of 3D reconstructed dendritic segments (green) containing spines (red) in unirradiated (0 cGy) and irradiated (5 and 30 cGy) mice brains. Multiple comparisons show that total spine numbers (left bar chart) and spine density (right bar chart) are significantly reduced after exposure to 5 or 30 cGy of 16 O particles. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 versus control; ANOVA. Adapted from Parihar et al. 39 . Permission to reproduce open-source figure per the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 .

To summarize, the health risks posed by the omnipresent exposure to space radiation are significant and include the “red” risks of cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and cognitive and behavioral decrements. While research on the late health risk of cancer is currently delayed, research on the in-flight effects of radiation on the cardiovascular system and CNS within the context of the space exposome are considered the highest priority and are the focus of investigations. Major knowledge gaps include the effects of radiation quality, dose-rate, and translation from animal models to human systems and evaluation of the requirement for medical countermeasure approaches to reduce the risk.

Spaceflight-Associated Neuro-ocular Syndrome

The Risk of Spaceflight-Associated Neuro-ocular Syndrome (SANS), originally termed the Risk of Vision Impairment Intracranial Pressure (VIIP), was first discovered about 15 years ago. VIIP was the original name used because the syndrome most noticeably affects a crewmember’s eyes and vision, and its signs can appear like those of the terrestrial condition idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH; which is due to increased intracranial pressure). Over time, it was realized that the VIIP name required an update. Most notably, SANS is not associated with the classic symptoms of increased intracranial pressure in IIH (e.g., severe headaches, transient vision obscurations, double vision, pulsatile tinnitus), and it has never induced vision changes that meet the definition of vision impairment, as defined by the National Eye Institute. In 2017, VIIP was renamed to SANS, a term that welcomes additional pathogenesis theories and serves as a reminder that this syndrome could affect the CNS well beyond the retina and optic nerve.

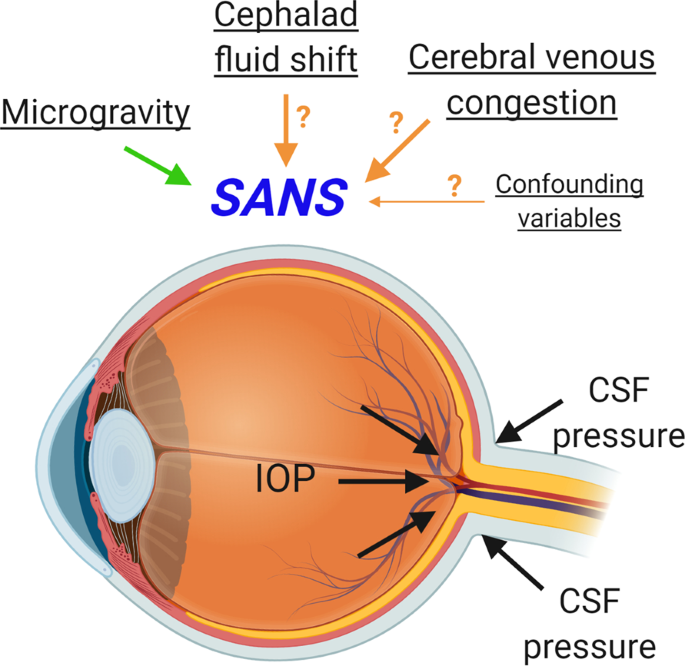

SANS presents with an array of signs, as documented in the HRP Evidence Report ( https://humanresearchroadmap.nasa.gov/evidence/reports/SANS.pdf ). Primarily, these include edema (swelling) of the optic disc and retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL), chorioretinal folds (wrinkles in the retina), globe flattening, and refractive error shifts 47 . Flight duration is thought to play a role in the pathogenesis of SANS, as nearly all cases have been diagnosed during or immediately after long-duration spaceflight (i.e., missions of 30 days duration or longer), although signs have been discovered as early as mission day 10 48 . Because of SANS, ocular data are nominally collected during ISS missions. For most ISS crewmembers, this testing includes optical coherence tomography (OCT), retinal imaging, visual acuity, a vision symptom questionnaire, Amsler grid, and ocular ultrasound (Fig. 7 ).

Image courtesy of NASA.

From a short-term perspective (e.g., a 6-month ISS deployment), SANS presents four main risks to crewmembers and their mission: optic disc edema (ODE), chorioretinal folds, shifts in refractive error, and globe flattening 49 . Approximately 69% of the US crewmembers on the ISS experience a > 20 µm increase in peripapillary retinal thickness in at least one eye, indicating the presence of ODE. With significant levels of ODE, a crewmember can experience an enlargement of his/her blind spots and a corresponding loss in visual function. To date, blind spots are uncommon and have not had an impact on mission performance.

If chorioretinal folds are severe enough and located near the fovea (the retina associated with central vision), a crewmember may experience visual distortions or reduced visual acuity that cannot be corrected with glasses or contact lenses, as noted in the SANS Evidence Report. Despite a prevalence of 15–20% in long-duration crewmembers, chorioretinal folds have not yet impacted astronauts’ visual performance during or after a mission. An on-orbit shift in refractive error is due to a shortening of the eye’s axial length (distance between the cornea and the fovea), and it occurs in about 16% of crewmembers during long-duration spaceflight. This risk is mitigated by providing deploying crewmembers with several pairs of “Space Anticipation Glasses” (or contact lenses) of varying power. On-orbit, the crewmember can then select the appropriate lenses to restore best-corrected visual acuity. Approximately 29% of long-duration crewmembers experience a posterior eyeball flattening, which is typically centered around the insertion of the optic nerve into the globe. Globe flattening can induce chorioretinal folds and shifts in refractive error, posing the respective risks described above.

From a longer-term perspective, SANS presents two main risks to crewmembers: ODE and chorioretinal folds. It is unknown if a multi-year spaceflight (e.g., a Mars mission) will be associated with a higher prevalence, duration, and/or severity of ODE compared to what has been experienced onboard the ISS. Since the retina and optic nerve are part of the CNS, if ODE is severe enough, the crewmember risks a permanent loss of optic nerve and RNFL tissue and thus, a permanent loss of visual function. It should be stressed that no SANS-related permanent loss of visual function has yet been discovered in any astronauts.

For choroidal folds, improvement generally occurs post-flight in affected crewmembers; however, significant folds can persist for 10 or more years after long-duration missions. Using MultiColor Imaging and autofluorescence capabilities of the latest OCT device, it was discovered recently that one crewmember’s longstanding (>5 years) post-flight choroidal folds have induced disruption to its overlying retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) 50 . The RPE is a monolayer of pigmented cells located between the vascular-rich choroid and the photoreceptor outer segments. This layer forms the posterior blood-brain barrier for the retina and is essential for maintaining the health of the posterior retina via the transport of nutrients and fluids, among other key functions. If the RPE is damaged, it could potentially lead to a degeneration of the local retina and progress to vision impairment.

Recent long-duration head-down tilt studies have shown potential for recreating SANS signs in terrestrial cohorts 51 . However, SANS is considered a pathology unique to spaceflight. In microgravity, fluid within the body is free to redistribute uniformly. This means that much of the fluid that normally pools in a person’s feet and legs due to gravity can transfer upward towards the head and cause a general congestion of the cerebral venous system. The central pathogenesis theories of SANS are based on these facts, but the actual cause(s) and pathophysiology of SANS are yet unknown 49 . The most publicized theory for SANS has been that cerebral spinal fluid outflow might be impeded, causing an overall increase in intracranial pressure (ICP) 47 , 52 . Other potential mechanisms (see Fig. 8 ) include cerebral venous congestion or altered folate-dependent 1-carbon metabolism via a cascade of mechanisms that may ultimately increase ICP or affect the response of the eye to fluid shifts 53 , 54 . Potential confounding variables for SANS pathogenesis include resistive exercise, high-sodium dietary intake, and high carbon dioxide levels.

Image created with BioRender.com.

Discovering patterns and trends in the SANS population has been difficult due to the relatively low number of crewmembers who have completed long-duration spaceflight. This is especially true for female astronauts. However, there is now enough evidence to state—emphatically—that SANS is not a male-only syndrome. OCT has been utilized onboard the ISS since late 2013, and it has revolutionized NASA’s ability to objectively detect and monitor SANS and build a high-resolution database of retinal and optic nerve head images. Through this technology, it has been recently discovered that that a majority of long-duration astronauts (including females) present with some level of ODE and engorgement of the choroidal vasculature 48 , 55 . The trends and patterns of these ocular anatomical changes may hold the key to deciphering the pathophysiology of SANS 48 , 55 .

Beginning in 2009 in response to SANS, all NASA crewmembers receive pre- and post-flight 3 Tesla magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and orbits. Based on these images, there is growing evidence that brain structural changes also occur during long-duration spaceflight. Most notably, a 10.7–14.6% ventricular enlargement (i.e., approximately a 2–3 ml increase) has been detected in astronauts and cosmonauts by multiple investigators 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 . On-orbit and post-flight cognitive testing have not revealed any systemic cognitive decrements associated with these anatomical changes. Moreover, additional research is required to determine if spaceflight-associated brain structural changes are related to ocular structural changes (i.e., SANS) or if the two are initiated by a common cause. Thus, until a relationship is established, SANS will be defined by ocular signs.

Future SANS medical operations, research, and surveillance will focus on: 1) determining the pathogenesis of the syndrome, 2) developing small-footprint diagnostic devices for expeditionary spaceflight, 3) establishing effective countermeasures, 4) monitoring for any long-term health consequences, and 5) discovering what factors make certain individuals more susceptible to developing the syndrome.

In summary, SANS is a top risk and priority to NASA and HRP. The primary SANS-related risk is ODE, due to the possibility of permanent vision impairment; however, choroidal folds also present a short- and long-term risk to astronaut vision. Shifts in refractive error are relatively common in long-duration missions, but crewmembers do not experience a loss of visual acuity if adequate correction is available. SANS affects female astronauts, not just males, although it is not yet known if SANS prevalence is equal between the sexes. There are no terrestrial pathologies identical to SANS, including IIH. Long-duration spaceflight is also associated with brain anatomical changes; however, it is not yet known whether these changes are related to SANS. Finally, the pathogenesis of SANS remains elusive; however, the main theories are related to increased intracranial pressure, ocular venous congestion, and individual anatomical/genetic variability.

Behavioral health and performance

The Risk of Adverse Cognitive and Behavioral Conditions and Psychiatric Disorders (BMed) focuses on characterizing and mitigating potential decrements in performance and psychological health resulting from multiple spaceflight hazards, including isolation and distance from earth. Spaceflight radiation is also recognized as contributing factor, particularly relative to a deep space planetary mission. The potential of additive or synergistic effects on the CNS resulting from simultaneous exposures to radiation, isolation and confinement, and prolonged weightlessness, is also of emerging concern ( https://humanresearchroadmap.nasa.gov/Risks/risk.aspx?i=99 ).

The official risk statement in the BMed Evidence Report notes, “ given the extended duration of future missions and the isolated, confined and extreme environments, there is a possibility that (a) adverse cognitive or behavioral conditions will occur affecting crew health and performance; and (b) mental disorders could develop should adverse behavioral conditions be undetected and unmitigated ” ( https://humanresearchroadmap.nasa.gov/Evidence/reports/BMED.pdf ). Primary outcomes for this risk include decrements in cognitive function, operational performance, and psychological and behavioral states, with the development of psychiatric disorders representing the least likely but one of the most consequential outcomes crew could experience in extended spaceflight. BMed is considered a “red” risk for planetary missions, given the long-duration of isolation, extended confinement, and exposure to additional stressors, including increased radiation exposure. The Human Factors and Behavioral Performance Element within HRP utilizes a research strategy that incorporates flight studies on astronauts, research in astronaut-like individuals and teams in ground analogs, and works with the Space Radiation Element to use animal models supporting research on combined spaceflight stressors.

While astronauts successfully accomplish their mission objectives and report very positive experiences living and working in space, some anecdotal accounts from current and past astronauts suggest that psychological adaptation in the long-duration spaceflight environment can be challenging. However, clinically significant operational decrements have not been documented to date, as noted in the BMed Evidence Report. Discrete events that have been documented include accounts of adverse responses to workload by Shuttle payload specialists, and descriptions of ‘hostile’ and ‘irritable’ crew in the 84-day Skylab 4 mission, as well as symptoms of depression reported on Mir by 2 of the 7 NASA astronauts.

Currently, potential stressors affiliated with missions to the ISS include extended periods of high workload and/or schedule shifting, physiological adaptation including fluid shifts caused by weightlessness and possibly, exposure to other environmental factors such as elevated carbon dioxide (see the BMed Evidence Report). While still physically isolated from home, the presence of the ISS in LEO facilitates a robust ground behavioral health and performance support team who offer services such as bi-weekly private psychological conferences and regular delivery of novel goods and surprises from home in crew care packages. Coupled with the relatively ample volume in the ISS, near-constant real-time communication with Earth, new crewmembers rotating periodically throughout missions, and relatively low levels of radiation exposure, —it is expected that behavioral challenges experienced today do not represent those that future crews will face during exploration missions.

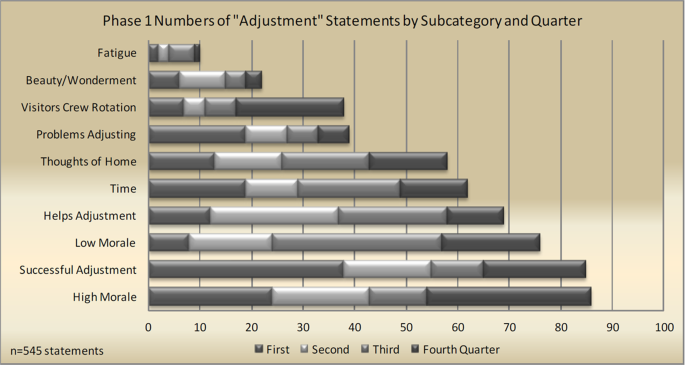

Nevertheless, the few completed behavioral studies on the ISS suggest that subjective perceptions of stress increase over time for some crewmembers, as shown by an in-flight study collecting subjective ratings of well-being and objective measures of fatigue 60 . Notably, it was found that astronaut ratings of sleep quality and sleep duration (also measured through visual analog scales) were found to be inversely related to ratings of stress. Another in-flight investigation seeking to characterize behavioral responses to spaceflight is the “Journals” study by Stuster 61 . This investigation provided a systematic approach to examining a rich set of qualitative data by evaluating astronaut journal entries for temporal patterns of across different behavioral states over the course of a mission (Fig. 9 ). Based on findings, some categories suggest temporal patterns while other categories of outcomes do not suggest a pattern relative to time, which may be due to no temporal relationship between outcomes and time, and/or various contextual factors within missions that negate the presence of such a relationship (e.g., visiting crew). An overall assessment by Stuster of negative comments relative to positive comments over time suggests evidence of a third quarter phenomenon in Adjustment alone, a category which reflects individual morale 61 .

Example bar graph showing distribution of journal entries related to general adjustment to the spaceflight enivronment during each quarter of an ISS mission 61 .

Other in-flight investigations support and expand upon contributors to increased stress on-orbit, including studies documenting reductions in sleep duration 62 , 63 and evaluation of crew responses to habitability and human factors during spaceflight 64 . While no studies have assessed potentially relevant mechanisms for behavioral or other reported symptoms, a recently completed investigation suggests neurostructural changes may be occurring in the spaceflight environment 56 . Magnetic resonance imaging scans were conducted on astronauts pre- and post-flight on both long-duration missions to the ISS or short-duration Shuttle missions. Assessments from a subgroup of participants ( n = 12) showed a slight upward shift of the brain after all long-duration flights but not after short-duration flights ( n = 6), and they also showed narrowing of cerebral spinal fluid spaces at the vertex after all long-duration flights ( n = 6) and in 1 of 6 crew after short-duration flights. A retrospective analysis of free water volume in the frontal, temporal, and occipital lobes before versus after spaceflight suggests alterations in free water distribution 65 . Whether there is a functionally relevant outcome as a result of such changes remains to be determined. Hence, while certain aspects of the spaceflight environment have been shown to increase some behavioral responses (e.g., reduced sleep owing to workload), the direct role of spaceflight-specific factors (such as fluid shifts and weightlessness) on behavioral outcomes or functional performance has not yet been established.

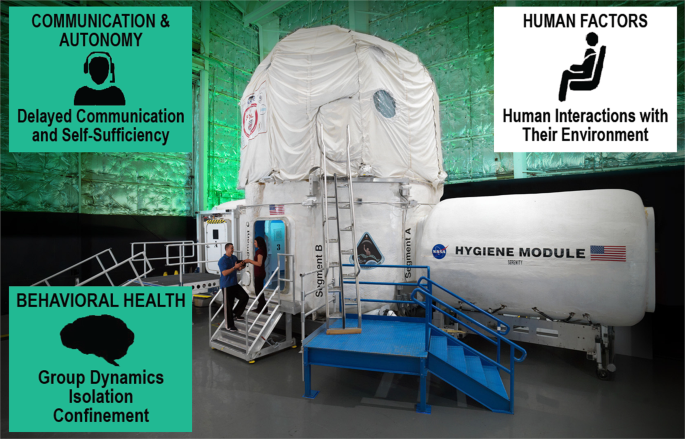

Future long-duration missions will pose threats to behavioral health and performance, such as extreme confinement in a small volume and communication delays, that are distinct from what is currently experienced on missions to the ISS. Analog research is concurrently underway to help further characterize the likelihood and consequence of an adverse behavioral outcome, and the effectiveness of potential countermeasures. Ground analogs, such as the Human Exploration Research Analog (HERA) at NASA Johnson Space Center, provide a test bed where controlled studies of small teams for periods up to 45 days, can be implemented (Fig. 10 ). HERA can be used to provide scenarios and environments analogous to space (e.g., isolation and confinement, communication delays, space food, and daily tasks and schedules) to investigate their effects on behavioral health, human factors, exploration medical capabilities, and communication and autonomy. Research in locations such as Antarctica also offer a unique opportunity to conduct research in less controlled but higher fidelity conditions. In general, these studies show an increased risk in deleterious effects such as decreased mood and increased stress, and in some instances, psychiatric outcomes (see the BMed Evidence Report).

HERA is used to simulate environments and mission scenarios analogous to spaceflight to investigate a variety of behavioral and human factors issues. Images courtesy of NASA.

In 2014, Basner and colleagues 62 completed an assessment of crew health and performance in a 520-day mission at an isolation chamber in Moscow at the Institute for Biomedical Problems (IBMP). During this simulated mission to Mars, the crew of six completed behavioral questionnaires and additional testing weekly. One of six (20%) crew reported depressive symptoms based on the Beck Depression Inventory in 93% of mission weeks, which reached mild-to-moderate levels in >10% of mission weeks. Additional indications of changes in mood were observed via the Profile of Mood States. Additionally, two crewmembers who had the highest ratings of stress and physical exhaustion accounted for 85% of the perceived conflicts, and other crew demonstrated dysregulation in their circadian entrainment and sleep difficulties. Two of the six crewmembers reported no adverse behavioral symptoms during the missions 62 . Building on this work, the NASA HRP and the IBMP have ongoing studies in the SIRIUS project, a series of long-duration ground-analog missions for understanding the effects of isolation and confinement on human health and performance ( http://www.nasa.gov/analogs/nek/about ).

Finally, more recent research in the HERA analog at Johnson Space Center is underway to assess not only individual, psychiatric outcomes but also changes in team dynamics and team performance over time (Fig. 10 ). A recent publication reported that conceptual team performance (e.g., creativity) seems to decrease over time, while performance requiring cognitive function and coordinated action improved 66 . While results from additional team studies in HERA are currently under review, the Teams Risk Evidence Report ( https://humanresearchroadmap.nasa.gov/Evidence/reports/Team.pdf ) provides a thorough overview of the evidence surrounding team level outcomes.

In summary, evidence from spaceflight and spaceflight analogs suggests that the BMed Risk poses a high likelihood and high consequence risk for exploration. Given the possible synergistic effects of prolonged isolation and confinement, radiation exposure, and prolonged weightlessness, mitigating such enhanced risks faced by future crews are of highest priority to the NASA HRP.

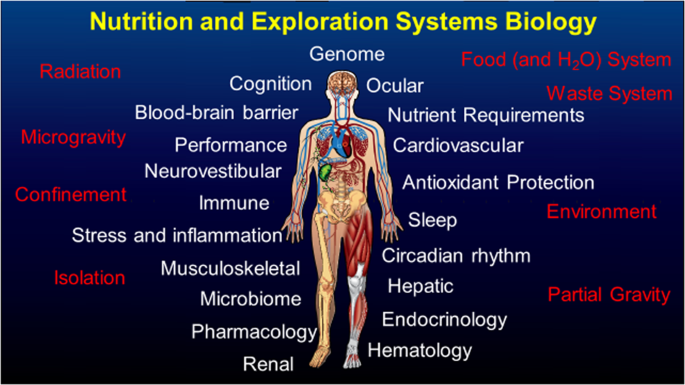

Inadequate food and nutrition

Historically, nutrition has driven the success—and often the failure—of terrestrial exploration missions. For space explorers, nutrition provides indispensable sustenance, provides potential countermeasures to some of the negative effects of space travel on human physiology, and also presents a multifaceted risk to the health and safety of astronauts ( https://humanresearchroadmap.nasa.gov/Evidence/other/Nutrition-20150105.pdf ).

At a minimum, the need to prevent nutrient deficiencies is absolute. This was proven on voyages during the Age of Sail, where scurvy—caused by vitamin C deficiency— killed more sailors than all other causes of death. On a closed (or even semi-closed) food system, the risk of nutrient deficiency is increased. On ISS missions, arriving vehicles typically bring some fresh fruits and/or vegetables to the crew. While limited in volume and shelf-life, these likely provide a valuable source of nutrients and phytochemicals every month or two. One underlying concern is that availability of these foods may be mitigating nutrition issues of the nominal food system, and without this external source of nutrients on exploration-class missions, those issues will be more likely to surface.