Science News by AGU

Apollo 11 Command Module Goes on Tour

Share this:

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

For William Harris, president and CEO of Space Center Houston, watching the Moon and stars was a big part of his growing up in rural Greenfield, Mass. As an inquisitive four-year-old back in July 1969, Harris remembers huddling with his family in front of a big, boxy, black-and-white television as NASA’s Apollo 11 lunar module Eagle landed on the Moon and as astronauts stepped onto its surface. His parents made sure that Harris and his siblings knew “this is history we’re watching,” he told Eos .

Now some of that history is on its way to his museum.

A Four-City Tour

Space Center Houston will be the first stop on a four-city tour of the Apollo 11 command module Columbia that carried the astronauts back to Earth, the Smithsonian Institution announced at a briefing on Wednesday. The module will arrive at the museum, along with more than 20 mission artifacts, in an exhibit titled Destination Moon: The Apollo 11 Mission on 24 October. That’s just in time to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the center, a Smithsonian Affiliate that opened its doors on 16 October 1992 and already displays some other national treasures, including the command module for Apollo 17 , the last mission to land astronauts on the Moon.

This marks the first time in 46 years that the Apollo 11 module is leaving the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum ( NASM ), officials from the museum said at the briefing held at the museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Va. The module that carried astronauts Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins back to Earth has been displayed at the museum’s Washington, D. C., location since 1976. It is temporarily in the Udvar-Hazy Center’s restoration hangar in preparation for the tour that celebrates the 50th anniversary of the Moon landing. The module, which FedEx will transport on the museum tour, previously traveled on a 50-state tour in 1970 and 1971 before it entered the NASM collection.

After Houston, the Apollo 11 module touches down at other Smithsonian Affiliates—the Saint Louis Science Center in Missouri; the Senator John Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh, Pa.; and the Museum of Flight in Seattle—before returning to the NASM in Washington, D. C., as a centerpiece in a new Destination Moon exhibit that will open in 2020.

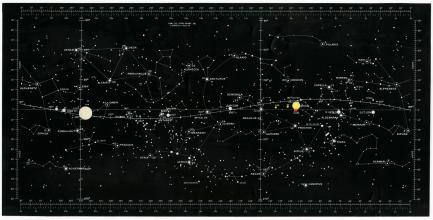

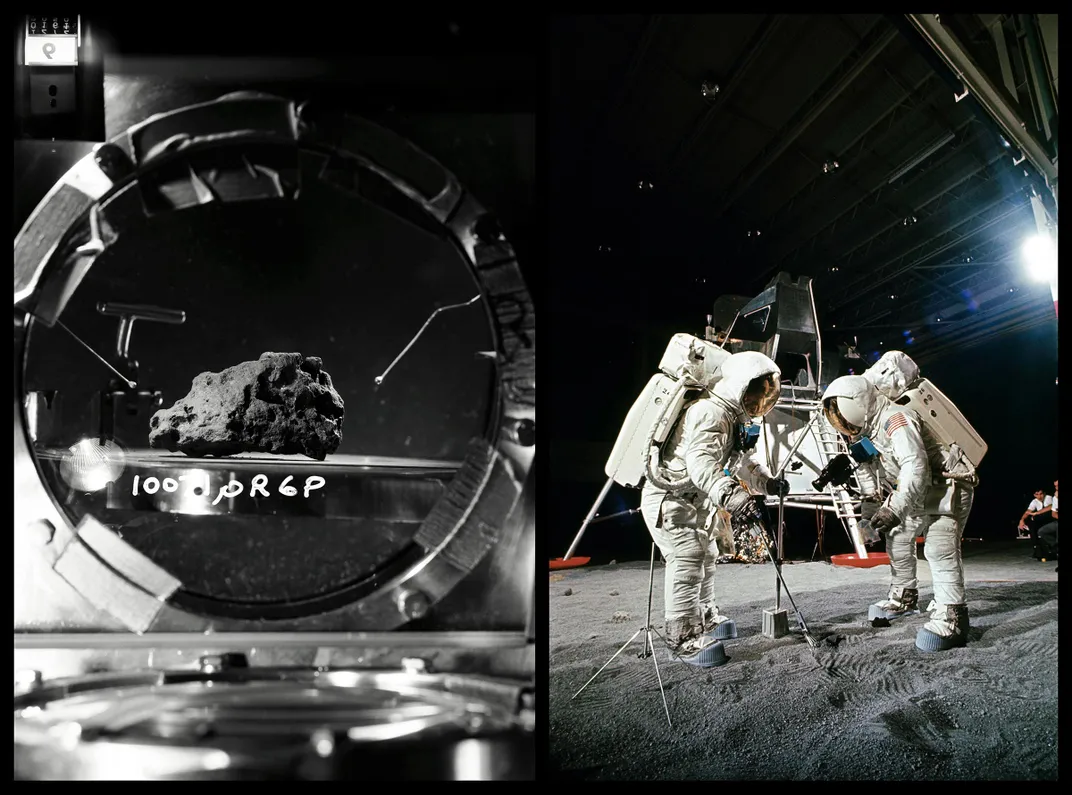

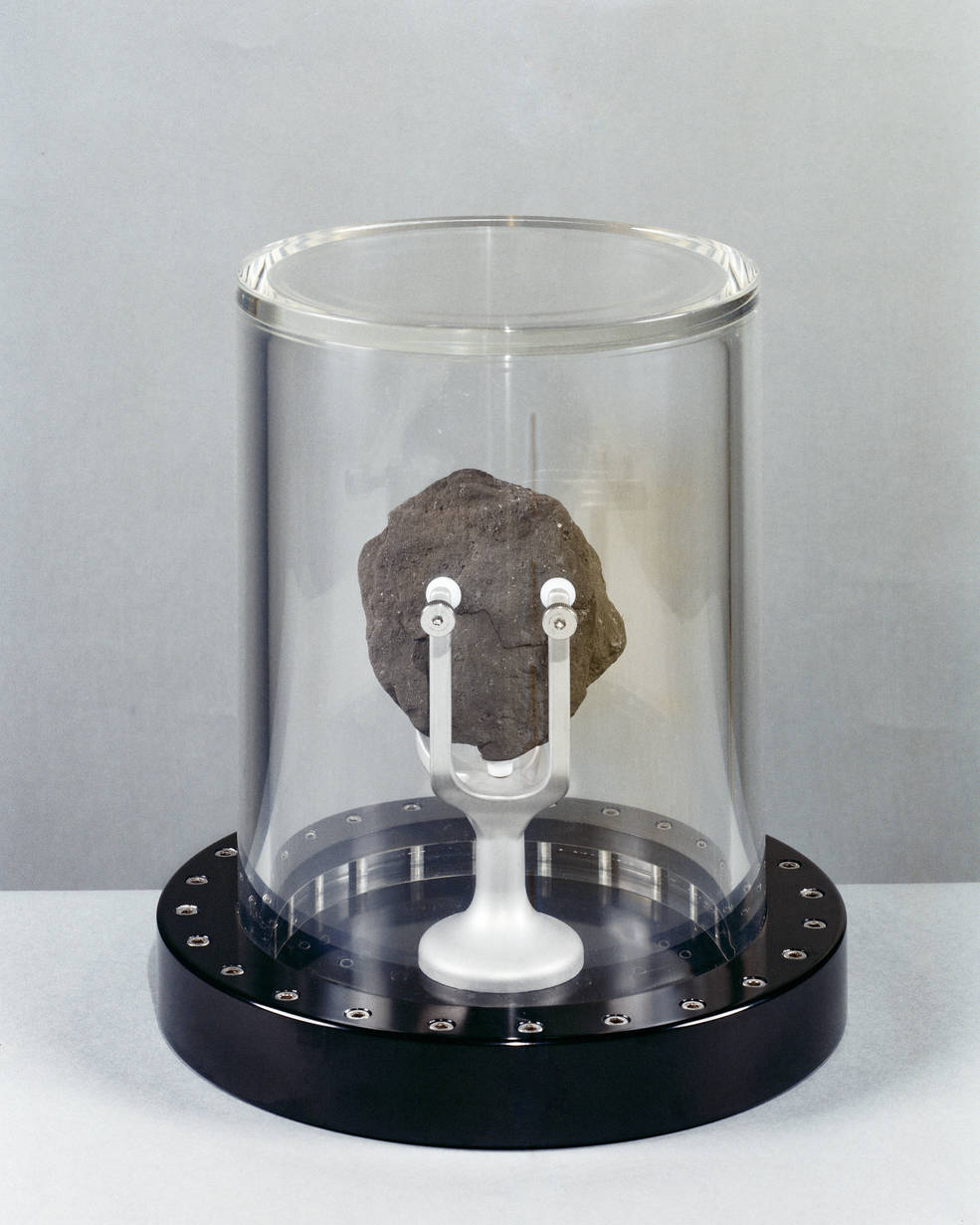

In addition to the module itself, the traveling exhibition includes a lunar sample return container used to carry Moon rock samples back to Earth; the star chart that shows the positions of the Sun, Moon, and stars at the time Apollo 11 was schedule to go to the Moon; Aldrin’s gloves; and an Apollo 11 F-1 injector plate, part of Apollo 11’s first-stage engine, that was recovered from the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean in 2013. The exhibit also includes an interactive 3-D tour , made from high-resolution scans of the spacecraft in 2016, that allows visitors to virtually explore the spacecraft, including its interior.

Designing the Exhibit

Michael Neufeld , senior curator for space history at NASM, told Eos that the traveling exhibit and the follow-on main exhibit back at the Smithsonian face a big challenge that didn’t exist when the Apollo exhibit opened in the 1970s. “No one under 50 remembers the Moon landing,” said Neufeld. “It’s not a personal experience” like it was back then.

Neufeld, who describes himself as “a total space buff,” was 18 years old at the time of the Apollo 11 mission. He was glued to a television set in his best friend’s house in Calgary, Canada, watching the news about the mission, including the nerve-racking landing as fuel dwindled and the subsequent Moon walk.

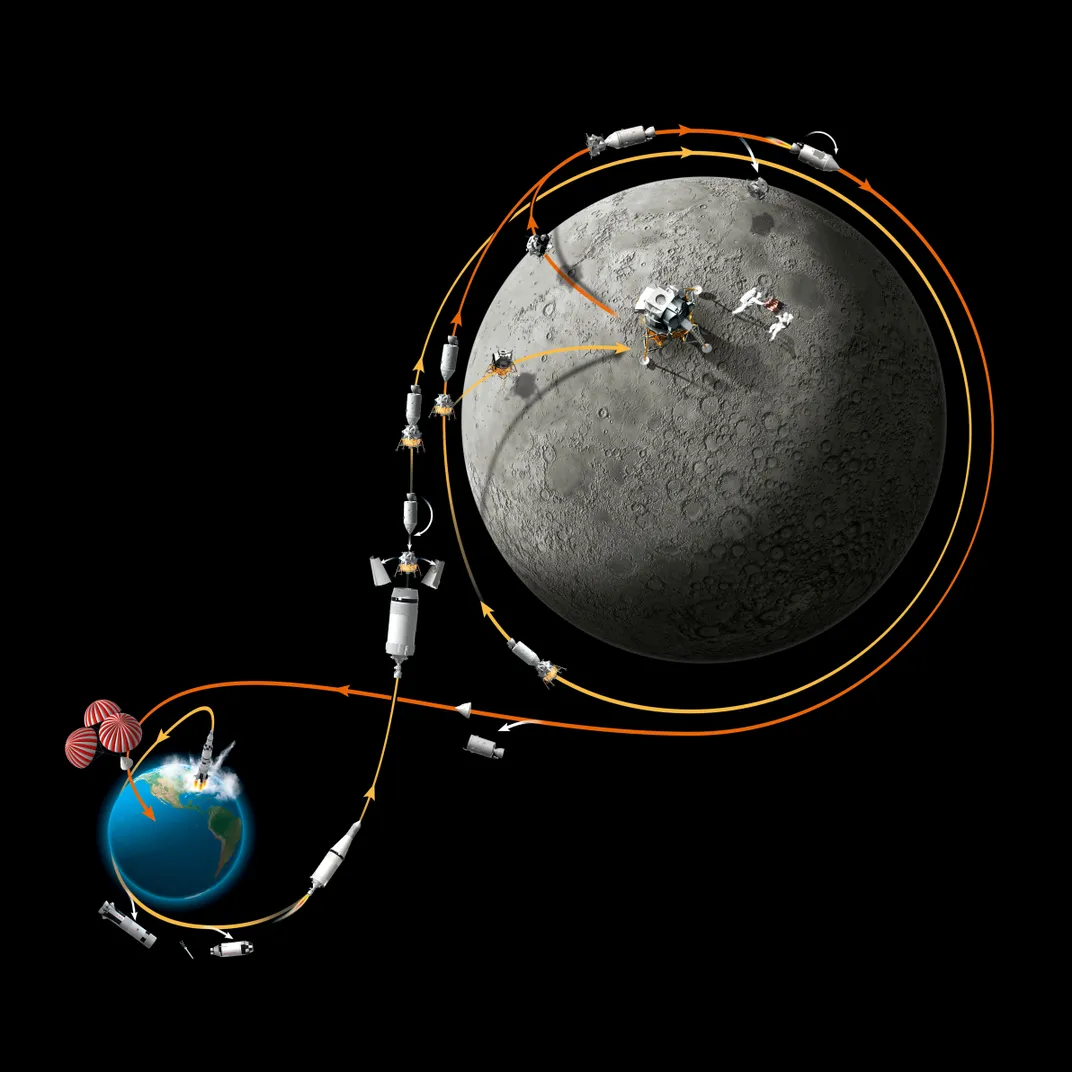

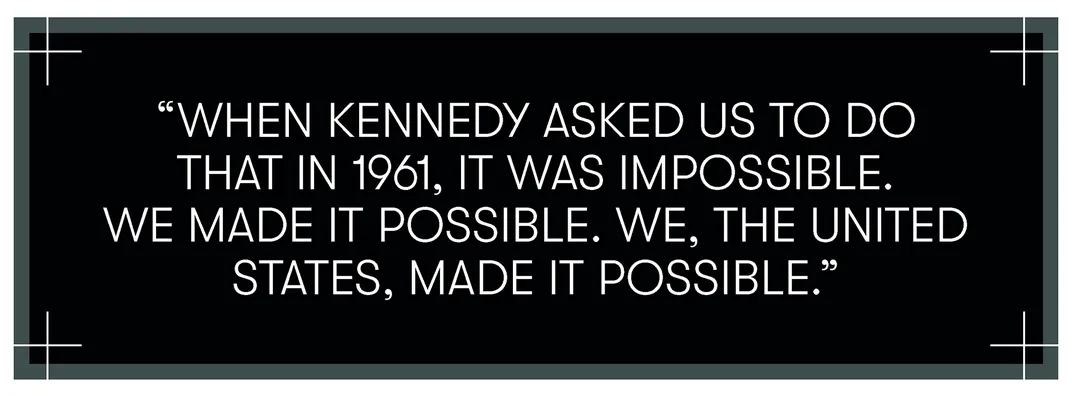

He said that the designers of the new exhibit, for which he is the lead curator, anticipated that now most people have only secondary knowledge about the Moon landing. The exhibit puts the Apollo missions in a broader historical context that includes President John F. Kennedy’s 1961 goal to send an astronaut to the Moon and back by the end of that decade and the efforts to conquer space during the Cold War with Russia.

The spacecraft represents “a great accomplishment,” said Neufeld. “People remember that and they think about that: Can we do something like that again?” he said.

NASM director John Dailey said he hopes that the upcoming tour of the spacecraft generates a lot of excitement. Last week, Bao Bao, a panda that had been at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo in Washington, D. C., “left via Federal Express for China. It was on all the major networks. Got good coverage. This is the capsule that went to the Moon. I would hope that at least we get similar coverage for its departure.”

—Randy Showstack ( @RandyShowstack ), Staff Writer

Correction, 27 February 2017: An earlier version of this article misstated the year Apollo 11 landed on the Moon, as well as a recent date. The article has been corrected.

Showstack, R. (2017), Apollo 11 command module goes on tour, Eos, 98 , https://doi.org/10.1029/2017EO068685 . Published on 27 February 2017.

Text © 2017. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.

Features from AGU Publications

Arctic warming is driving siberian wildfires, forecasting caldera collapse using deep learning, an all-community push to “close the loops” on southern ocean dynamics.

SPECIAL EXHIBIT

Entry: Exhibit Ticket Required | Location: Union Terminal

Don’t miss the final stop of Apollo 11’s national tour

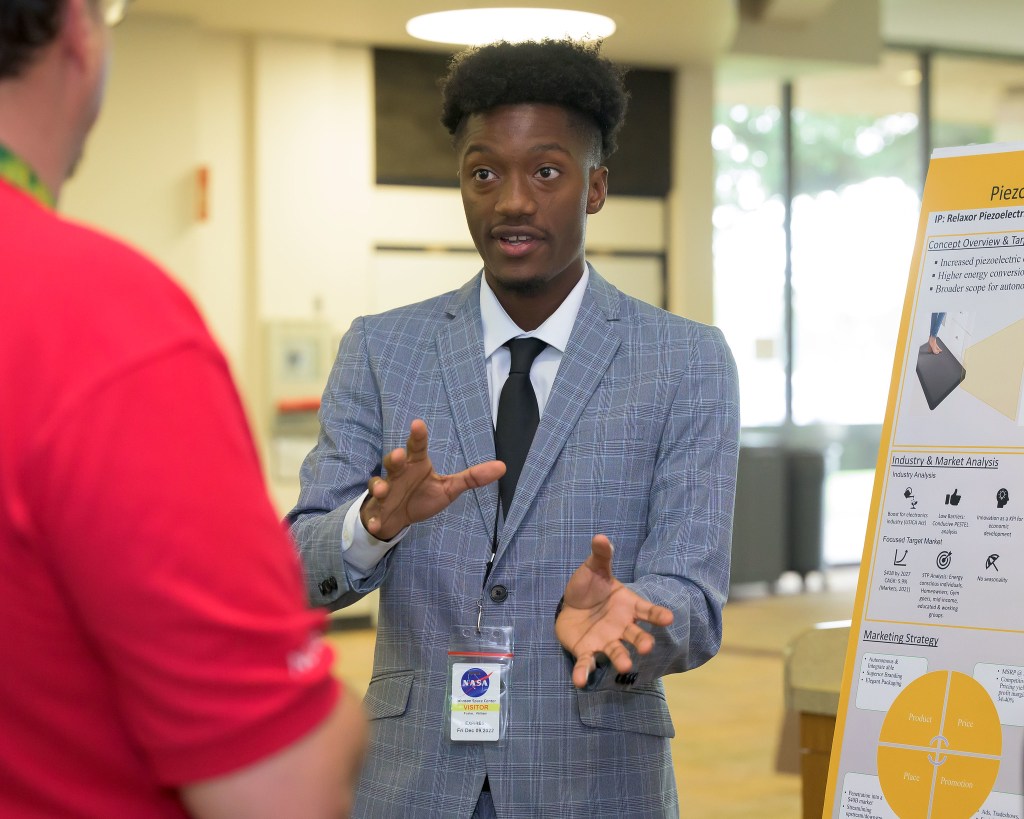

On July 24, 1969, the Apollo 11 mission met President Kennedy’s 1961 challenge of “landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the earth” before the end of the decade. Destination Moon: The Apollo 11 Mission explores and honors that great achievement using genuine flown artifacts from the Apollo 11 mission on loan from the National Air and Space Museum. Featuring the Apollo command module Columbia — the only portion of the historic spacecraft to survive the lunar journey — the exhibition explores the birth and development of the American space program and the space race in time for the 50th anniversary of humankind’s greatest scientific achievement.

Destination Moon gives guest the rare opportunity to see artifacts that made the 953,000-mile journey possible, like Buzz Aldrin’s gold-plated extravehicular helmet visor and thermal-insulated gloves. The dizzying star chart that helped Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins navigate the historic journey and the rucksack and survival kit that accompanied the astronauts are also included. The star of the exhibition is the Columbia command module, on display outside the National Air and Space Museum for the first time since 1976.

“Artifacts so authentic you can almost smell the moon dust on them!"

“So crazy to stand inches away from the command module!"

Key artifacts

Command Module Columbia

Manufacturer: North American Rockwell Primary Materials: aluminum alloy, stainless steel, titanium Dimensions: 10 feet, 7 inches x 12 feet, 10 inches. 9,130 lbs. -->

The only part of the Apollo 11 spacecraft to return intact to Earth. It was the three-person crew’s living quarters for most of the mission, from Cape Kennedy, to the Moon’s orbit, to splashdown in the Pacific Ocean.

Aldrin’s Extravehicular Visor

Visor materials: gold-plated polycarbonate, UV-coated polycarbonate

The A7-L Lunar Extravehicular Visor Assembly consists of a polycarbonate shell onto which the cover, visors, hinges, eyeshades and latch are attached. It has two visors, one covered with a thermal control coating and the other with a gold optical coating. It also has two steel side sunshields, which could be raised and lowered independently. It provided impact, micrometeoroid, thermal, ultraviolet and infrared light protection.

Aldrin’s Extravehicular Gloves

Primary exterior materials: beta cloth, Chromel-R, Velcro, rubber-silicone compound

The gloves were constructed of an outer shell of Chromel-R fabric with thermal insulation to provide protection while handling extremely hot or cold objects. The blue fingertips were made of silicone rubber to provide sensitivity. The inner glove was of a rubber/neoprene compound, into which the restraint system was integrated.

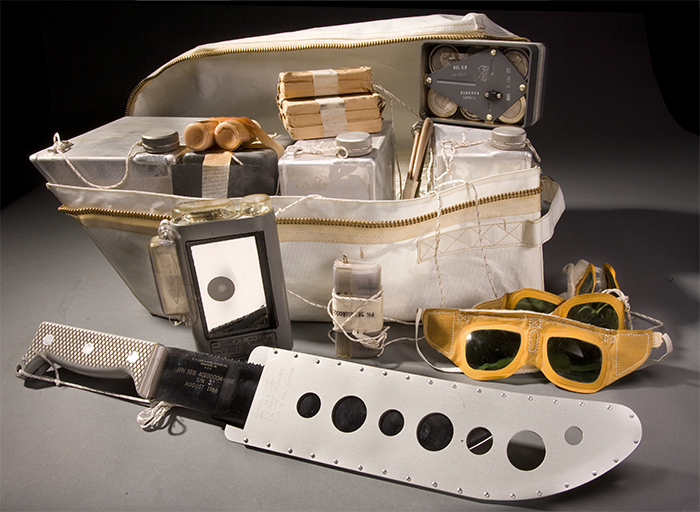

Rucksack #1, Survival Kit

Each Apollo mission was equipped with two rucksacks providing equipment to allow for crew survival on Earth for up to 48 hours after landing. This is the first of the two rucksacks flown on Apollo 11. It includes three water containers, one radio beacon with spare battery, three pairs of sunglasses, six packages of desalted chemicals, one desalter kit, two survival lights, one machete and two bottles of sunscreen.

“If you’re a space nut, this exhibit is totally worth it!"

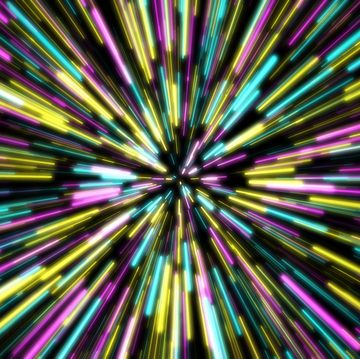

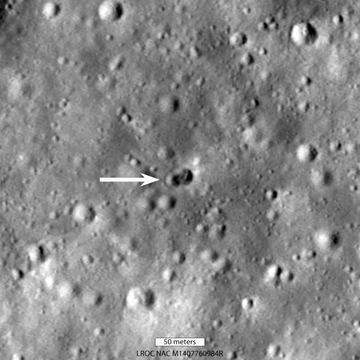

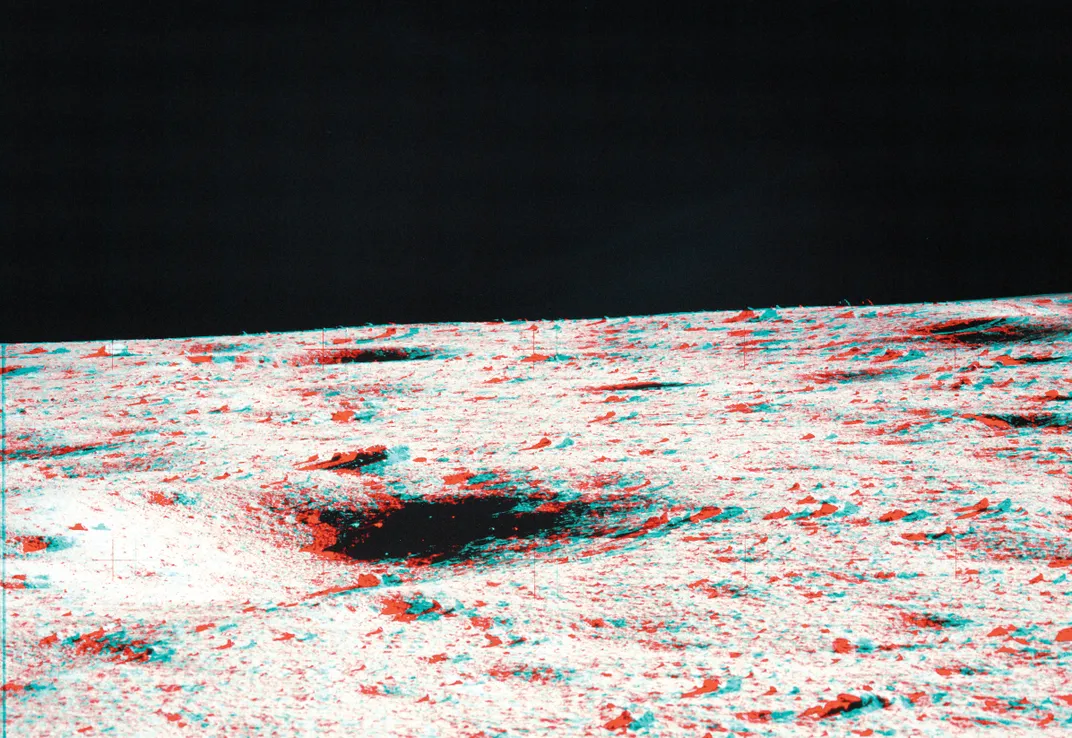

A New Moon Rises

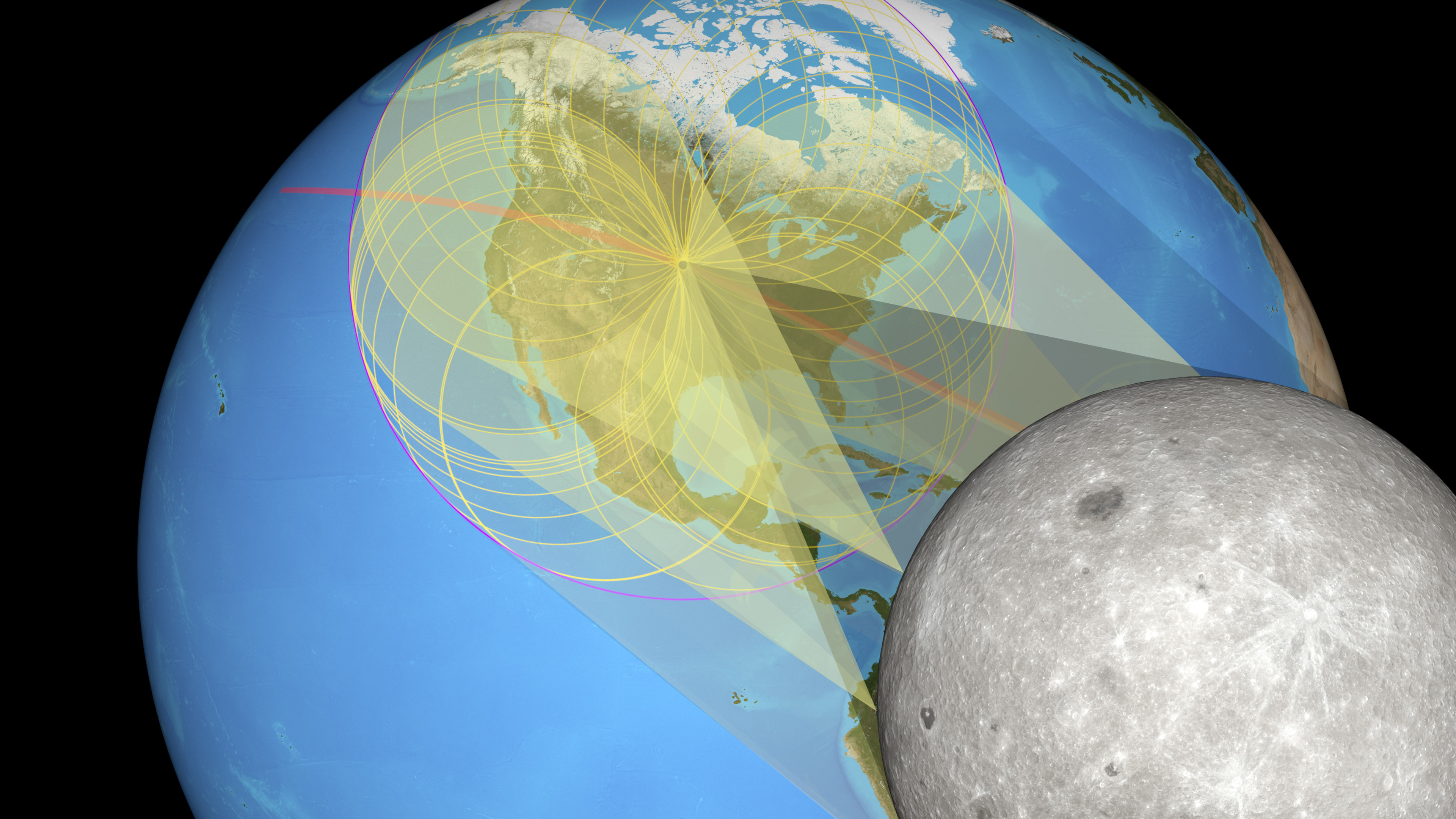

The Moon is not the same place as when astronauts last stepped on foot on it. A New Moon Rises , a companion gallery to Destination Moon presented by the Smithsonian, features stunning large-scale photographs of the lunar surface captured by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Cameras (LROC) between 2009 and 2015. The highly detailed photographs reveal a celestial neighbor that is surprisingly dynamic and full of grandeur and wonder.

A New Moon Rises was created by the National Air and Space Museum and the Arizona State University, and is organized by the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service.

A New Moon Rises is included with admission to Destination Moon: The Apollo 11 Mission .

Tickets for Destination Moon

BUY TICKETS

Members receive discounts!

Member tickets for Maya are only $12.50!-->

Become a Member today to save on programs, exhibits and films throughout CMC.

BECOME A MEMBER

Member Perk

Hey Members! Do you want to see Destination Moon while avoiding the busy times during its final days? Come see Destination Moon starting at 9 a.m. on Saturday, February 1, 8 and 15. The exhibit will also stay open late with the last entry at 6 p.m. through February 17. Exhibition open through February 17, 2020.

Destination Moon Discounts

- AAA Members can receive $2 off Destination Moon: The Apollo 11 Mission and $1 off Museum Admission when they present their membership card at the box office or by providing their AAA Membership number when purchasing tickets over the phone or use code: 3ADISCMOON when you purchase your tickets online.*

- Military persons, including active, retired, veterans, and family, receive $3 off Destination Moon when they present their military ID at box office.

* Must purchase Destination Moon: The Apollo 11 Mission ticket and a Museum Admission ticket as a combo in order to redeem this discount.

Join the conversation using #CMCmoon

The exhibit looks great - and it's in Neil's home state! 👍 #ApolloXI https://t.co/Kd3FLLeOc1 — Buzz Aldrin (@TheRealBuzz) October 4, 2019

Don’t miss the Columbia command module’s last stop on its Smithsonian traveling tour. #DestinationMoon is now on exhibit at the @CincyMuseum through February 17, 2020. https://t.co/fFY8L15KIk — Michael Collins (@AstroMCollins) February 10, 2020

Monday — Sunday 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.

Open daily with the exception of Christmas Day and Thanksgiving Day.

Plan your experience

General information

Accessibility

Videos & Extras:

- Event Details

Around the World with the Apollo 11 Crew 6/22/2019

The global tour aboard the Museum's Air Force One

Two months after Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins voyaged to the Moon, they undertook another strenuous but rewarding journey: the GIANTSTEP-APOLLO 11 Presidential Goodwill Tour. Serving as President Richard Nixon’s official representatives, the Apollo 11 crew visited over twenty countries on every continent in less than two months.

Author Teasel E. Muir-Harmony recounts Nixon and National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger’s hands-on role in selecting tour stops and joining the crew as they flew aboard Air Force One (The Museum of Flight’s SAM 970 ) to nearly thirty cities in just forty-five days. From laying wreaths at the Christopher Columbus monument in Spain to highlighting Australian contributions to the first lunar landing in Sydney, the astronauts amplified the message that the Moon landing was “for all mankind,” at every stop.

Days after the Apollo 11 crew returned home, Kissinger called the tour one of the nation’s “effective policy vehicles.” Through the story of the GIANTSTEP tour, this talk will reflect on the deep interconnection between spaceflight and American diplomacy, from Project Apollo to today.

The Teasel will also sign copies of her new book, Apollo to the Moon: A History in 50 Objects.

FREE with Museum admission.

To honor our newest exhibition, Destination Moon: The Apollo 11 Mission, we're proud to introduce a new program series to complement the stories behind the artifacts, people, and places that made the Moon landing possible.

To The Moon! program series will feature a wide-ranging selection of scientists, space experts, historians, authors, pilots, and more, who will speak about lunar exploration, past, present, and future.

See All Programs

sign up for our newsletter

This website may use cookies to store information on your computer. Some help improve user experience and others are essential to site function. By using this website, you consent to the placement of these cookies and accept our privacy policy.

Site Navigation

Smithsonian announces national tour of exhibition celebrating the 50th anniversary of the moon landing.

Version en españo l

The Apollo 11 command module Columbia—the only portion of the historic spacecraft to complete the first mission to land a man on the moon and safely return him to Earth—will leave the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum for the first time in 46 years for the traveling exhibition “Destination Moon: The Apollo 11 Mission.”

The exhibition’s two-year national tour will celebrate the approaching 50th anniversary of the mission and explore the birth and development of the American space program and the space race.

The planned tour, organized by the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service (SITES), will bring the command module and more than 20 one-of-a-kind artifacts from the historic mission to some of the top museums in the country:

- Space Center Houston—Oct. 14, 2017–March 18, 2018

- Saint Louis Science Center—April 14–Sept. 3, 2018

- Senator John Heinz History Center, Pittsburgh—Sept. 29, 2018–Feb. 18, 2019

- The Museum of Flight, Seattle—March 16–Sept. 2, 2019

The Apollo 11 command module will return to a place of honor in the new exhibition “Destination Moon,” scheduled to open in 2021.

Through original Apollo 11-flown objects, models, videos and interactives, visitors will learn about the historic journey of the Apollo 11 crew—Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins and Buzz Aldrin. “Destination Moon” will include an interactive 3-D tour, created from high-resolution scans of Columbia performed at the Smithsonian in spring 2016. The interactives will allow visitors to explore the entire craft including its intricate interior, an interior that has been inaccessible to the public until now.

On July 24, 1969, Apollo 11 met President John F. Kennedy’s 1961 challenge of “landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the Earth.” The exhibition will explore what led the United States to accept this challenge and how the resulting 953,054-mile voyage to the moon and back was accomplished just eight years after the program was authorized. “Destination Moon” will examine the mission and shed a light on some of the more than 400,000 people employed in NASA programs who worked through the trials, tragedies and triumphs of the 20 missions from 1961 to 1969 before Apollo 11.

The tour will mark the first time Columbia will leave the National Air and Space Museum since the museum opened to the public in 1976. Before entering the collection, the command module traveled on a 50-state tour throughout 1970 and 1971 covering more than 26,000 miles. It then went on display in the Smithsonian’s Arts and Industries Building before the current National Air and Space Museum was built on the National Mall.

“Destination Moon: The Apollo 11 Mission” is made possible by the support of Jeff and MacKenzie Bezos, Joe Clark, Bruce R. McCaw Family Foundation, the Charles and Lisa Simonyi Fund for Arts and Sciences, John and Susann Norton, and Gregory D. and Jennifer Walston Johnson. Transportation services for “Destination Moon” are provided by FedEx.

The traveling exhibition previews part of a new gallery opening at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., which is slated to open in 2021. “Destination Moon” at the museum will tell the story of human exploration of the moon, from ancient dreams to the Apollo program to the missions happening right now.

All of the museums on the tour are Smithsonian Affiliates—members of a national outreach program that develops long-term collaborative partnerships with museums, educational and cultural organizations to enrich communities with Smithsonian resources.

SITES has been sharing the wealth of Smithsonian collections and research programs with millions of people outside Washington, D.C., for 65 years. SITES connects Americans to their shared cultural heritage through a wide range of exhibitions about art, science, and history, which are shown wherever people live, work and play. For exhibition description and tour schedules, visit sites.si.edu .

The National Air and Space Museum building on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., is located at Sixth Street and Independence Avenue S.W. The museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center is located in Chantilly, Va., near Washington Dulles International Airport. Attendance at both buildings combined exceeded 9 million in 2016, making it the most visited museum in America. The museum’s research, collections, exhibitions and programs focus on aeronautical history, space history and planetary studies. Both buildings are open from 10 a.m. until 5:30 p.m. every day (closed Dec. 25).

Alison Wood

202-633-2376

Jennifer Schommer

202-633-3121

- News Releases

- Media Contacts

- Photos and Video

- Fact Sheets

- Visitor Stats

- Secretary and Admin Bios

- Filming Requests

Media Events

Newsdesk RSS Research News RSS

Media Use Only

Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins pose in front of the Columbia at the National Air and Space Museum in 1979.

National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution

Apollo 11 command module Columbia on temporary cradle.

Photo by Eric Long, National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution

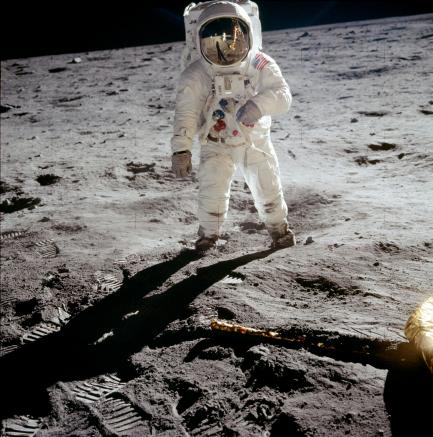

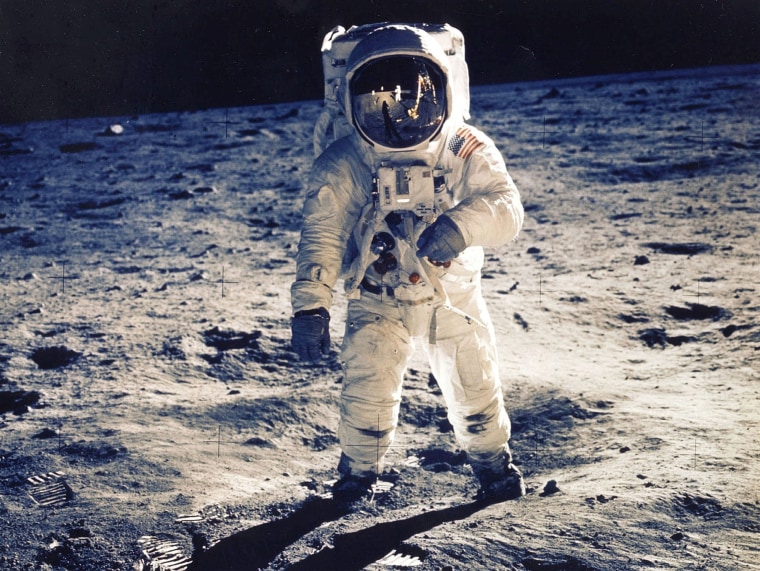

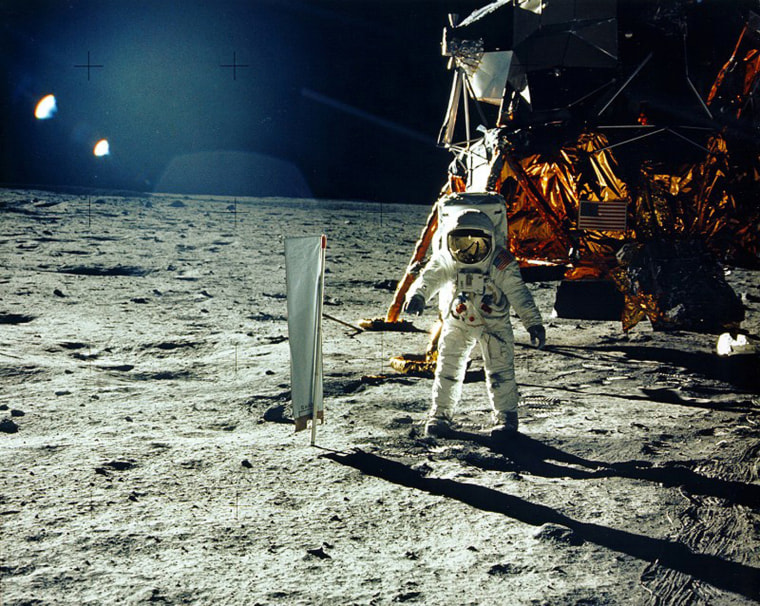

Astronaut Buzz Aldrin walks on the surface of the moon near the leg of the lunar module Eagle during the Apollo 11 extravehicular activity (EVA).

Photo courtesy of NASA

Astronaut Michael Collins wore the Omega Speedmaster Chronograph during the Apollo 11 mission.

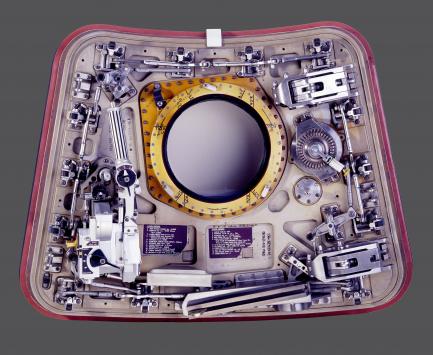

The hatch served as the entry and exit point to the command module Columbia on the launch pad and after landing.

The interior of the Apollo 11 Command Module.

Photo by Eric Long, National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution

The extravehicular (EV) gloves made for and worn by astronaut Buzz Aldrin, lunar module pilot of the Apollo 11 mission in July, 1969.

The chart shows the positions of the sun, moon, and stars at the time Apollo 11 was scheduled to leave Earth orbit and head for the moon.

Credit: National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution

One of two rucksacks filled with equipment to help the crew survive for up to 48 hours in the event of an emergency landing on Earth.

The extravehicular visor assembly worn by astronaut Buzz Aldrin on the lunar surface during the historic Apollo 11 mission in July, 1969.

Smithsonian Extends Apollo 11 Spacecraft Tour, Adds Stop in Cincinnati

The spacecraft that carried the crew of the first moon landing to and from Earth 50 years ago has just had its current mission extended.

The Smithsonian, which has been touring the command module "Columbia" as part of its "Destination Moon: The Apollo 11 Mission" exhibition, made the surprise announcement on Friday (June 14) that the capsule will stay on the road beyond the 50th anniversary of the historic lunar flight. The next and new final stop for the spacecraft, together with more than 20 related artifacts , will be in Cincinnati, Ohio.

"I am very happy that the Cincinnati Museum Center will be home to Destination Moon this fall," said Myriam Springuel, director of the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service and Smithsonian Affiliations, at a press conference at the Cincinnati Museum Center on Friday.

Related: Apollo 11 at 50: A Complete Guide to the Historic Moon Landing Mission

The exhibition, which is currently at The Museum of Flight in Seattle for the 50th anniversary of the moon landing, will be on display in Cincinnati beginning Sept. 28 through Feb. 17, 2020.

"Cincinnati, and Union Terminal specifically, is the perfect place for these national treasures," said Carol Armstrong, widow of Apollo 11 astronaut Neil Armstrong.

The exhibition's extension came about for the same reason the command module was deployed on tour two years ago. The exhibit previews part of a new gallery at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., which is slated to debut to the public in 2022.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The museum is in the midst of a major transformation of its permanent galleries . A change in the construction schedule has opened our ability to add one additional stop to the original four-city tour," explained Springuel.

Before arriving in Seattle, the Destination Moon exhibition was hosted by Space Center Houston in Texas, the Saint Louis Science Center in Missouri and the Senator John Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The original plan was for the artifacts to return to the National Air and Space Museum's Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in September, to await their permanent installation in the new Destination Moon gallery.

"Bringing [the traveling exhibition] Destination Moon to Ohio is a natural fit," said Springuel. "The state, after all, is 'the birthplace of aviation.'"

In addition to Orville and Wilbur Wright, the Dayton-natives who invented the first powered aircraft to take flight, and John Glenn , who became the first American to orbit Earth before representing Ohio in the U.S. Senate, there is also the state's connection to the first human to walk on the moon.

" Neil Armstrong began his career in the space program at Lewis Research Center [now Glenn Research Center] in Cleveland," said Springuel.

"There could be no more appropriate place, both because of the venue but also because Carol and Neil chose to make Cincinnati their home," said Senator Rob Portman (R-OH). "He is from Wapakoneta, so he is not from Cincinnati originally, but this is where he chose to live and work, including teaching at the University of Cincinnati and starting his businesses. So we are so proud to have that heritage here and that legacy of Neil Armstrong and the first step on the moon."

The Cincinnati Museum Center is also home to Armstrong's piece of the moon.

"At one point around 2005, my father was given the honor of taking a moon rock and giving it to some organization. He had no constraints to where that moon rock might go and he chose to give it here ," said Armstrong's son, Mark. "I am just really pleased that Cincinnati and the Cincinnati Museum Center has been chosen to be the final destination on this incredible exhibit's way back to Washington, D.C."

The Cincinnati Museum Center recently unveiled a new permanent exhibit, the Neil Armstrong Space Exploration Gallery, dedicated to celebrating the Apollo 11 mission . The gallery, which now features interactive elements, original equipment and artifacts, will expand in 2020 to look toward the future of space exploration.

The command module's arrival in Cincinnati will mark the second time the capsule has been in Ohio. Nearly 80,000 people saw the spacecraft when NASA displayed it in 1970 at a state fair in Columbus as part of a 50-state tour.

"Now, 47 years after entering the Smithsonian's collection, we are honored to take it on the road once again and bring it back to Ohio," said Springuel.

In addition to the command module, the Destination Moon: The Apollo 11 Mission exhibition also features the spacesuit visor assembly and gloves that Buzz Aldrin wore on the moon, the Omega Speedmaster chronograph that Michael Collins wore in lunar orbit and an Apollo lunar sample return container that Armstrong and Aldrin used to return the first moon rocks to Earth.

"This is an incredible opportunity to see these iconic pieces of history," said Elizabeth Pierce, president and CEO of the Cincinnati Museum Center . "We are honored to bring this national treasure to Cincinnati and inspire our region for a giant next leap."

- Catch These Events Celebrating Apollo 11 Moon Landing’s 50th Anniversary

- Reading Apollo 11: The Best New Books About the US Moon Landings

- Lego's Epic Apollo 11 Lunar Lander Set in Photos!

Follow collectSPACE.com on Facebook and on Twitter at @ collectSPACE . Copyright 2019 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: [email protected].

Robert Pearlman is a space historian, journalist and the founder and editor of collectSPACE.com , an online publication and community devoted to space history with a particular focus on how and where space exploration intersects with pop culture. Pearlman is also a contributing writer for Space.com and co-author of "Space Stations: The Art, Science, and Reality of Working in Space” published by Smithsonian Books in 2018. He previously developed online content for the National Space Society and Apollo 11 moonwalker Buzz Aldrin, helped establish the space tourism company Space Adventures and currently serves on the History Committee of the American Astronautical Society, the advisory committee for The Mars Generation and leadership board of For All Moonkind. In 2009, he was inducted into the U.S. Space Camp Hall of Fame in Huntsville, Alabama. In 2021, he was honored by the American Astronautical Society with the Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History.

SpaceX Crew-9 astronaut launch delayed to Sept. 25

Watch Rocket Lab launch 5 'Internet of Things' satellites today

'Space for Birds': Astronaut Roberta Bondar captures avian habitats from Earth, in air and on orbit in new book (interview)

Most Popular

- 2 SpaceX Crew-9 astronaut launch delayed to Sept. 25

- 3 Harvest Moon Supermoon lunar eclipse delights skywatchers worldwide (photos)

- 4 Watch Rocket Lab launch 5 'Internet of Things' satellites today

- 5 SpaceX launches 2 European navigation satellites, lands rocket (video)

This week, we announced that the Apollo 11 Command Module Columbia , the original spacecraft that carried the first astronauts to walk on the Moon, and more than 20 additional flown artifacts from the Apollo 11 mission, will go on a national tour to four major American cities: Houston, Saint Louis, Pittsburgh, and Seattle. The tour coincides with the 50 th anniversary of Apollo 11 in July of 1969. While this will mark the first time the spacecraft has left the Smithsonian since it was added to the collection in 1971, it is not the first time the Command Module Columbia toured the United States.

The Command Module Columbia is among the most prized and popular artifacts in the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum collection. It was launched atop a Saturn V rocket on July 16, 1969 carrying astronauts Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins on the first lunar landing mission. The spacecraft was their home as they traveled to the Moon and back. On July 24, 1969, it reentered Earth’s atmosphere and splashed down in the Pacific Ocean to bring all three astronauts safely home.

Before it was entrusted to the Smithsonian for preservation and public display, Columbia went on another, now largely forgotten, journey. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) organized and executed an ambitious public tour of a Moon rock, Neil Armstrong’s lunar extravehicular activity (EVA) spacesuit, several small items that had returned from the mission, and the Command Module Columbia . Stopping at 49 state capitals, the District of Columbia, and Anchorage Alaska, the tour provided Americans with a unique opportunity to view and marvel at these historic items. When the tour was over, in 1971, Columbia was relocated to Washington, DC. It has been cared for and displayed by the Smithsonian Institution ever since, until now.

As you prepare to see Columbia in one of the four stops of the tour, relive its first journey across the US here with pages from NASA’s 1971 report for the “Fifty-State National Tour” along with images from that period.

Custom Image Caption

The final report of NASA’s Fifty-State Tour issued in June 1971.

According to this, 3 ¼ million Americans attended the tour.

The Command Module, and supporting artifacts, traveled nearly 26,000 miles for the tour, including trips by sea to Alaska and Hawaii.

Hawaii had the largest turnout with 135,000 people visiting.

Each state put their own spin on hosting the tour. In Dover, Delaware, a colonial regiment band opened the exhibition.

The tour prompted many states to declare “Space Week” or “Apollo Days” for the duration of the tour in their state.

A Norman Rockwell painting of the Lunar Module on the Moon was included in the tour.

Maryland had the lowest turnout with 32,500 visitors.

Alaska and Hawaii had the highest turnout of visitors.

To get to Hawaii and Alaska, the Command Module spent nearly a month at sea for each trip.

Apollo 11 Tour visits Jefferson City, Missouri July 1970. Courtesy of the Missouri State Archives

Astronaut Buzz Aldrin, a Congressman, and Mrs. Richard Ichord look at the Command Module. Courtesy of the Missouri State Archives

Astronauts Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins at the opening of the tour in Jefferson City, Missouri in July 1970. Courtesy of the Missouri State Archives

Ribbon cutting for the exhibition in Jefferson City, Missouri. Courtesy of the Missouri State Archives

Are you planning to visit Columbia when it goes on tour this October?

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.

Thank you. You have successfully signed up for our newsletter.

Error message, sorry, there was a problem. please ensure your details are valid and try again..

- Get Involved

- Host an Event

- Free Timed-Entry Passes Required

- Terms of Use

clock This article was published more than 7 years ago

Apollo 11 command takes off for 4-city tour through 2019

The Smithsonian’s prized Apollo 11 command module will leave the National Air and Space Museum for the first time in 46 years when it becomes the star attraction of a two-year, four-city touring exhibition, “Destination Moon: The Apollo 11 Mission.”

The module Columbia – the only piece of the spacecraft to complete the first mission to land a man on the moon and return him to Earth – will be the centerpiece of the exhibition that will open Oct. 14 in Houston before moving to St. Louis, Pittsburgh and Seattle.

The artifacts will be on the road for the first part of a planned, multi-year renovation of the Air and Space Museum and for the 50th anniversary of the historic mission.

[Air and Space Museum’s makeover estimated at $1 billion]

“It did things that up until then were hardly imaginable, and it stoked tremendous excitement about the possibilities of technology in the future,” Smithsonian Secretary David J. Skorton said about the Apollo 11 mission. The traveling exhibition will allow the museum “to reach out to the much greater number of people in their hometowns, in their communities, so they can share the magic of the Smithsonian.”

More than 20 objects associated with the mission and its crew members Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins and Buzz Aldrin will be part of the exhibition, according to Senior Curator Michael J. Neufeld. They include Aldrin’s extravehicular gloves,, a medical kit, a “rock box” used to bring back the first samples of the moon and Collins’s chronograph.

The Columbia had been on view at the Air and Space Museum on the National Mall from its opening in 1976 until last December, when it was moved to the conservation lab at the museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center near Dulles Airport. It will be studied, conserved and stabilized for nine months before the national tour begins at the Space Center Houston.

The exhibition will then travel to the Saint Louis Science Center from April 14-Sept. 3 2018 and to the Senator John Heinz History Center from Sept. 29, 2018-Feb. 18, 2019. It will be at the Museum of Flight in Seattle from March to Sept. 2, 2019, where it will celebrate the mission’s 50 th anniversary.

Before it entered the museum’s collection, the Columbia command module toured all 50 states in 1970 and 1971, covering more than 26,000 miles. It then went on view in the Smithsonian’s Arts and Industries Building before the current Air and Space Museum opened. Its tour coincides with the planned start of a major renovation of the building on the Mall.

Museum officials have engineered a special traveling crate for this four-city tour. The module and its exhibition case weigh more than 13,000 pounds.

The museum will host an “Apollo on the Move” celebration at Udvar-Hazy on March 4 from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. Visitors will be allowed inside the restoration hangar to meet staff and view the other conservation projects. Special movie screenings and family-friendly programs will highlight the event.

Take a 3D Tour Inside the Apollo 11 Command Module

Take a look inside the tiny capsule that carried three astronauts hundreds of thousands of miles to the moon and back.

Yesterday, we celebrated the 47th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission, the historic initiative that landed astronauts on the moon. The only part of the Apollo 11 spacecraft to make it back to earth was the command module "Columbia," where astronauts Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins and Buzz Aldrin lived throughout the eight day mission.

Since its landing on July 24th, 1969, the Columbia has been kept sealed in plexiglass at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, DC. That is, until recently, when the software company Autodesk was allowed a rare opportunity to use their high-tech 3D scanning equipment to create a simulation of the spacecraft that anyone on the internet can explore.

This was no easy feat. The spacecraft was tiny, with many nooks and crannies that required robotic equipment to explore. Autodesk ended up collecting 7 terabytes of data using many technologies, which they then had to laboriously piece together to form the 3D model.

Scanning the spacecraft revealed secrets that even the Smithsonian curators didn't know. They were able to see "graffiti" written by the crew members on the inside of the craft, including a calendar and notes on the transmissions between the Columbia and Earth.

Explore the inside of the Columbia and take a guided tour over at the Smithsonian Institute's website .

Snorkeler Finds Huge Rocket Panel on Remote Island

Starship Explosion Blew Open the Ionosphere

This Laser Could Unlock Interstellar Travel

The World’s Biggest Rocket Just Got Closer to Mars

New Warp Drive Concept Is More Fact Than Fiction

NASA's Ion Thruster Could Spawn a Space Revolution

An Engineer Says He’s Overcome Earth’s Gravity

Scientists Get Serious in Search for Warp Drive

A Chinese Rocket Took an Unknown Item to the Moon

The Pentagon Really Wants a Nuclear Spacecraft

Cylinder on Australian Beach is Part of a Rocket

Why the Aerospike Engine Is the Future of Rockets

Apollo 11 Tour Puts Famed Moon Mission Back in Spotlight

Nearly 50 years after NASA's first moon landing, the Apollo 11 command module is set to tour the U.S. Here's a look back at the mission.

Charred and battered from the forces of atmospheric reentry, the Apollo 11 command module Columbia has been at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. since the museum's 1976 opening. For the next two years, Columbia will travel 8,000 miles and visit four museums, arriving at the last in time to mark the 50th anniversary of the first lunar landing in 2019.

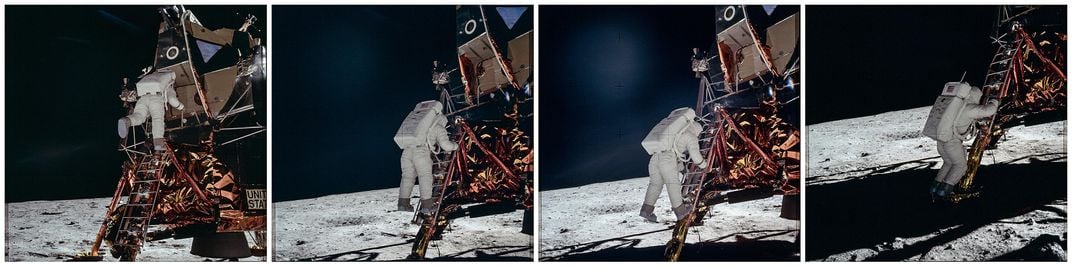

Astronaut Edwin "Buzz" Aldrin became the second man to walk on the lunar surface after he and fellow Apollo 11 astronaut Neil Armstrong successfully landed the lunar module on July 20, 1969.

The huge, 363-feet tall Saturn V rocket launches the Apollo 11 mission from Launch Complex 39A at Florida's Kennedy Space Center on July 16, 1969.

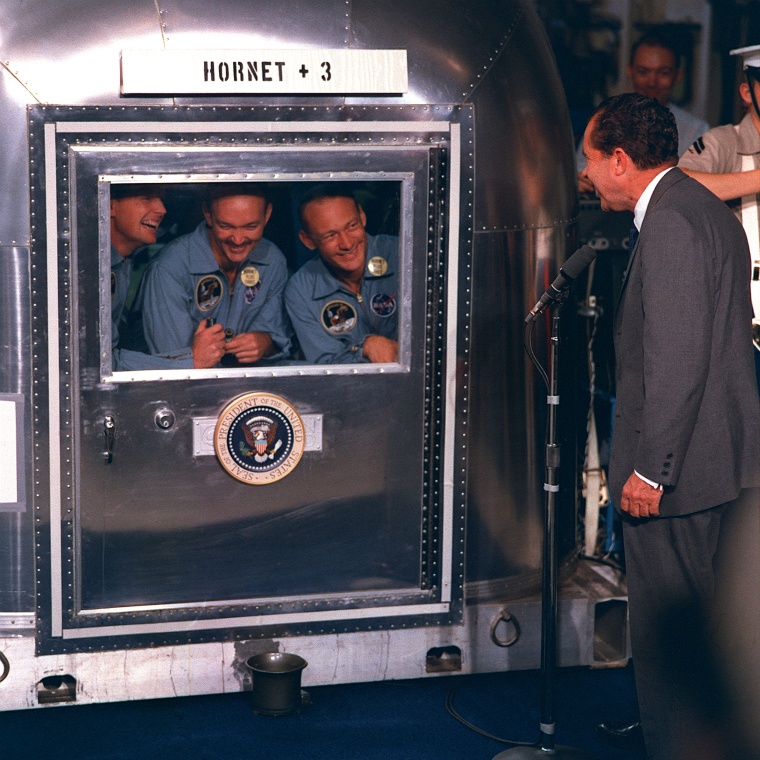

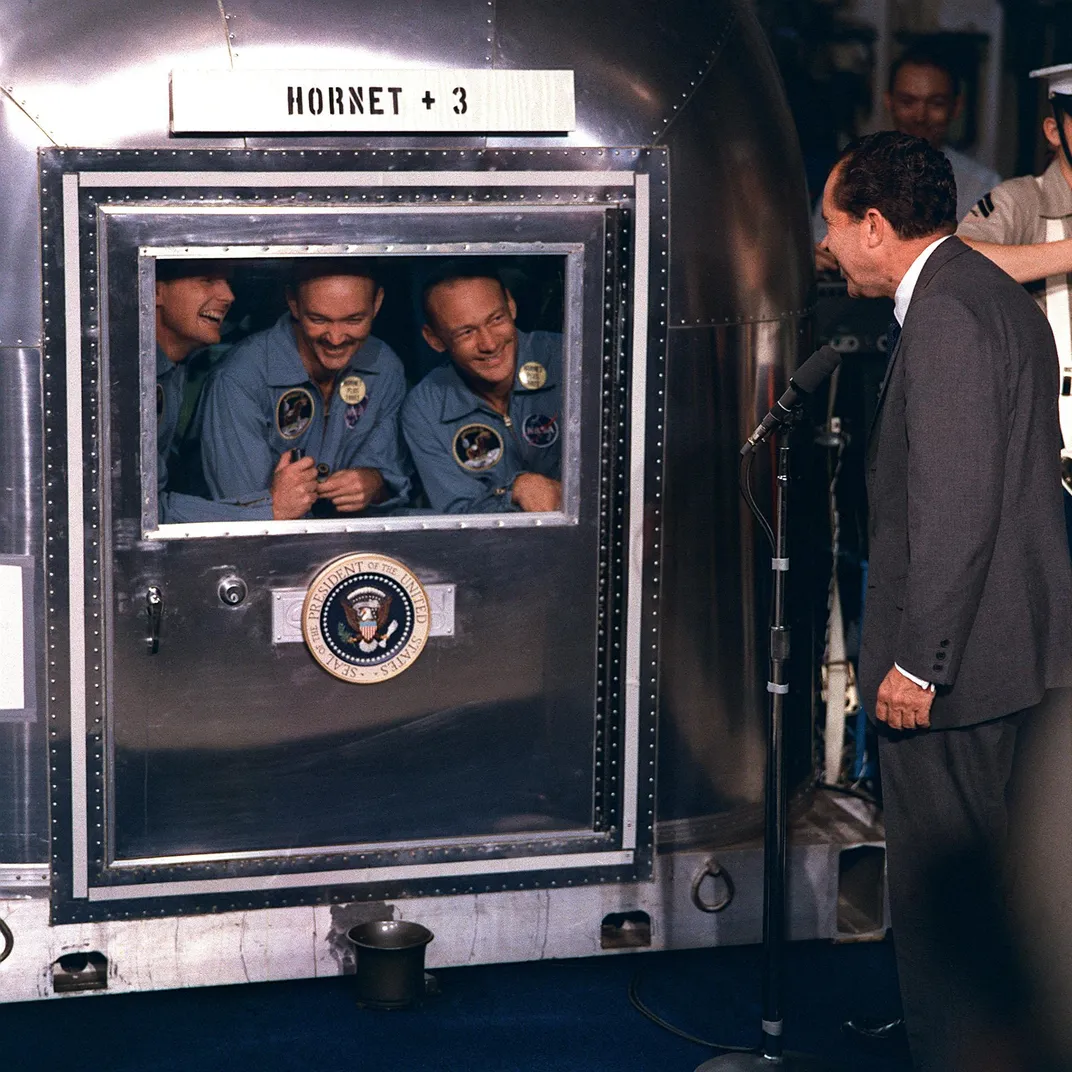

President Richard Nixon welcomes the Apollo 11 astronauts back to Earth aboard the USS Hornet, prime recovery ship for the historic Apollo 11 lunar landing mission. Already confined to the Mobile Quarantine Facility are, left to right: Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins, and Buzz Aldrin.

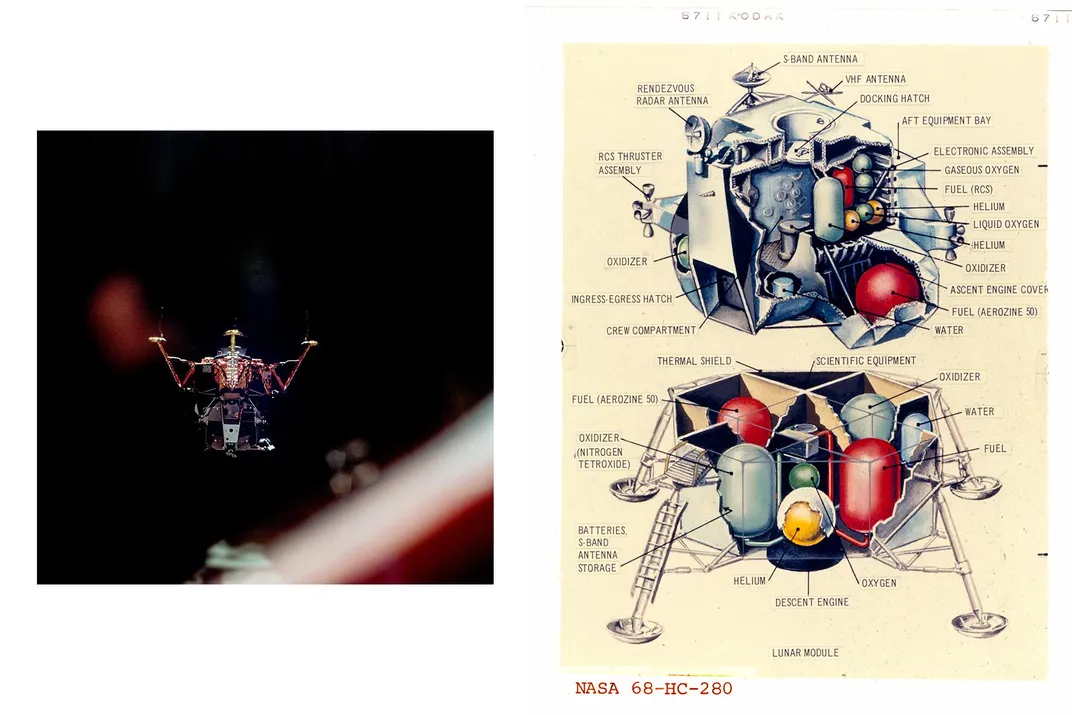

The Apollo 11 lunar module ascent stage, with Armstrong and Aldrin aboard, is photographed from the Command and Service Module during rendezvous in lunar orbit on July 21, 1969. The lunar module was making its docking approach to the CSM. Collins remained with the CSM in lunar orbit while the other two crewmen explored the moon's surface.

An estimated 10,000 people gathered to watch giant screens in New York's Central Park and cheer as Neil Armstrong took man's first step on the moon on July 20, 1969.

Aldrin stands beside a solar wind experiment next to the lunar module after he and Armstrong became the first men to land on the moon's surface.

This view from the Apollo 11 spacecraft shows Earth rising above the moon's horizon.

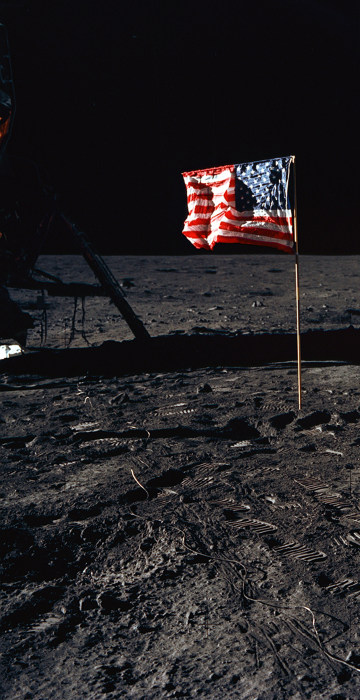

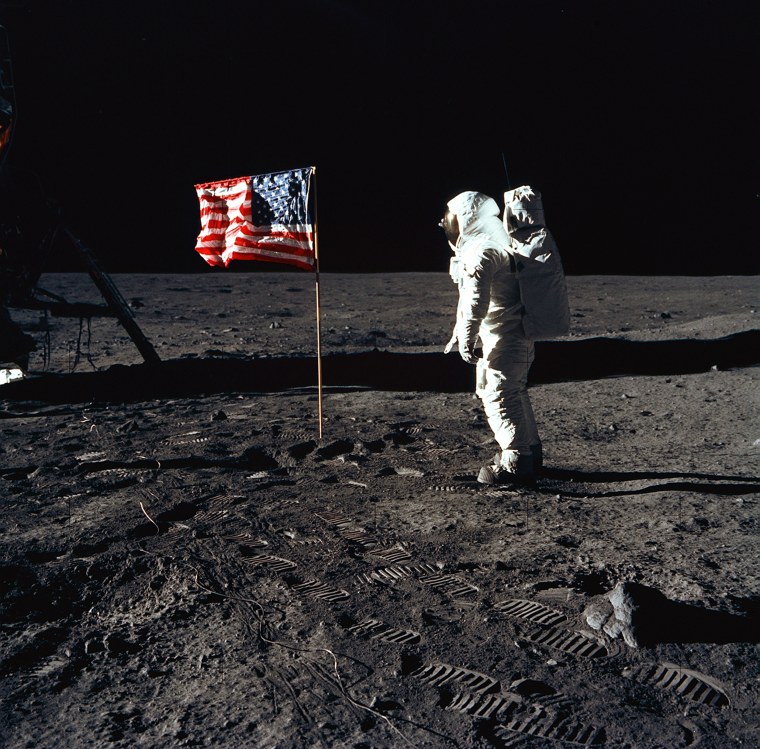

Aldrin poses for a photograph beside the United States flag after the historic landing on July 20, 1969.

PHOTOS: The Evolution of the Spacesuit

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

The Two-Way

Apollo 11 space capsule is going on another mission.

Nell Greenfieldboyce

The Apollo 11 command module Columbia sits in the Mary Baker Engen Restoration Hangar in Virginia, where it is undergoing conservation. Dane Penland/National Air and Space Museum/Smithsonian Institution hide caption

The Apollo 11 command module Columbia sits in the Mary Baker Engen Restoration Hangar in Virginia, where it is undergoing conservation.

The space capsule that took the first moonwalkers on their historic adventure is getting ready to take off on another trip — its first tour of the United States in more than 40 years.

The Apollo 11 command module is the spacecraft that Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins rode in to the moon and back in 1969. To celebrate the upcoming 50th anniversary of that achievement, the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum is sending the space capsule to four different museums around the country.

It's the first time the space capsule, called Columbia, will have left the museum since it opened to the public in 1976.

The traveling exhibit also will include objects such as the helmet and gloves that Aldrin wore during his moonwalk, a "rock box" that the astronauts used to bring back some of the first samples ever from a heavenly body and the watch that Collins wore during his lonely time orbiting the moon while Aldrin and Armstrong explored the lunar surface.

"This is the spacecraft that brought the three astronauts home from the first landing on the moon, so it's one of the Smithsonian's most important artifacts," says Michael Neufeld , a senior curator at the museum.

In 1970 and 1971, before it came to the Smithsonian, the capsule went on a 50-state tour. This time around, it will be going here:

- Space Center Houston — Oct. 14, 2017–March 18, 2018

- St. Louis Science Center — April 14–Sept. 3, 2018

- Senator John Heinz History Center, Pittsburgh — Sept. 29, 2018–Feb. 18, 2019

- The Museum of Flight, Seattle — March 16–Sept. 2, 2019

Those museums were picked for a variety of reasons, including the fact that they had the capacity to display such a large, heavy object.

"All of the venues actually had to submit engineering documentation to make sure that the floor load was one that could support not just the Columbia, but also the rest of the traveling exhibit," says Kathrin Halpern , a project director at the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service. "It's a very special artifact. And it does weigh a lot. The command module, on its traveling ring, is over 13,600 pounds."

She says this is likely a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see the command module outside of Washington, D.C. When it returns, Columbia will be the centerpiece of a new " Destination Moon " exhibit that will open in 2021 to tell the story of lunar exploration from ancient times to today.

- Neil Armstrong

- Buzz Aldrin

Apollo at 50: We Choose to Go to the Moon

A Smithsonian magazine special report

Science | June 2019

What You Didn’t Know About the Apollo 11 Mission

From JFK’s real motives to the Soviets’ secret plot to land on the Moon at the same time, a new behind-the-scenes view of an unlikely triumph 50 years ago

:focal(1000x263:1001x264)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/90/f0/90f0ab1d-d802-4e18-9ab8-deb642692615/jun2019_b05_apollo11.jpg)

Charles Fishman

The Moon has a smell. It has no air, but it has a smell. Each pair of Apollo astronauts to land on the Moon tramped lots of Moon dust back into the lunar module—it was deep gray, fine-grained and extremely clingy—and when they unsnapped their helmets, Neil Armstrong said, “We were aware of a new scent in the air of the cabin that clearly came from all the lunar material that had accumulated on and in our clothes.” To him, it was “the scent of wet ashes.” To his Apollo 11 crewmate Buzz Aldrin, it was “the smell in the air after a firecracker has gone off.”

All the astronauts who walked on the Moon noticed it, and many commented on it to Mission Control. Harrison Schmitt, the geologist who flew on Apollo 17, the last lunar landing, said after his second Moonwalk, “Smells like someone’s been firing a carbine in here.” Almost unaccountably, no one had warned lunar module pilot Jim Irwin about the dust. When he took off his helmet inside the cramped lunar module cabin, he said, “There’s a funny smell in here.” His Apollo 15 crewmate Dave Scott said: “Yeah, I think that’s the lunar dirt smell. Never smelled lunar dirt before, but we got most of it right here with us.”

Moon dust was a mystery that the National Aeronautics and Space Administration had, in fact, thought about. Cornell University astrophysicist Thomas Gold warned NASA that the dust had been isolated from oxygen for so long that it might well be highly chemically reactive. If too much dust was carried inside the lunar module’s cabin, the moment the astronauts repressurized it with air and the dust came into contact with oxygen, it might start burning, or even cause an explosion. (Gold, who correctly predicted early on that the Moon’s surface would be covered with powdery dust, also had warned NASA that the dust might be so deep that the lunar module and the astronauts themselves could sink irretrievably into it.)

Among the thousands of things they were keeping in mind while flying to the Moon, Armstrong and Aldrin had been briefed about the very small possibility that the lunar dust could ignite. “A late-July fireworks display on the Moon was not something advisable,” said Aldrin.

Armstrong and Aldrin did their own test. Just a moment after he became the first human being to step onto the Moon, Armstrong had scooped a bit of lunar dirt into a sample bag and put it in a pocket of his spacesuit—a contingency sample, in the event the astronauts had to leave suddenly without collecting rocks. Back inside the lunar module the duo opened the bag and spread the lunar soil on top of the ascent engine. As they repressurized the cabin, they watched to see if the dirt started to smolder. “If it did, we’d stop pressurization, open the hatch and toss it out,” Aldrin explained. “But nothing happened.”

The Moon dust turned out to be so clingy and so irritating that on the one night that Armstrong and Aldrin spent in the lunar module on the surface of the Moon, they slept in their helmets and gloves, in part to avoid breathing the dust floating around inside the cabin.

By the time the Moon rocks and dust got back to Earth—a total of 842 pounds from six lunar landings—the odor was gone from the samples, exposed to air and moisture in their storage boxes. No one has quite figured out what caused the odor to begin with, or why it was so like spent gunpowder, which is chemically nothing like Moon rock. “Very distinctive smell,” Apollo 12 commander Pete Conrad said. “I’ll never forget. And I’ve never smelled it again since then.”

In 1999, as the century was ending, the historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. was among a group of people who was asked to name the most significant human achievement of the 20th century. In ranking the events, Schlesinger said, “I put DNA and penicillin and the computer and the microchip in the first ten because they’ve transformed civilization.” But in 500 years, if the United States of America still exists, most of its history will have faded to invisibility. “Pearl Harbor will be as remote as the War of the Roses,” said Schlesinger. “The one thing for which this century will be remembered 500 years from now was: This was the century when we began the exploration of space.” He picked the first Moon landing, Apollo 11, as the most significant event of the 20th century.

The trip from one small planet to its smaller nearby moon might someday seem as routine to us as a commercial flight today from Dallas to New York City. But it is hard to argue with Schlesinger’s larger observation: In the chronicle of humanity, the first missions by people from Earth through space to another planetary body are unlikely ever to be lost to history, to memory, or to storytelling.

The leap to the Moon in the 1960s was an astonishing accomplishment. But why? What made it astonishing? We’ve lost track not just of the details; we’ve lost track of the plot itself. What exactly was the hard part?

The answer is simple: When President John F. Kennedy declared in 1961 that the United States would go to the Moon, he was committing the nation to do something we simply couldn’t do. We didn’t have the tools or equipment—the rockets or the launchpads, the spacesuits or the computers or the micro-gravity food. And it isn’t just that we didn’t have what we would need; we didn’t even know what we would need. We didn’t have a list; no one in the world had a list. Indeed, our unpreparedness for the task goes a level deeper: We didn’t even know how to fly to the Moon. We didn’t know what course to fly to get there from here. And as the small example of lunar dirt shows, we didn’t know what we would find when we got there. Physicians worried that people wouldn’t be able to think in micro-gravity conditions. Mathematicians worried that we wouldn’t be able to calculate how to rendezvous two spacecraft in orbit—to bring them together in space and dock them in flight both perfectly and safely.

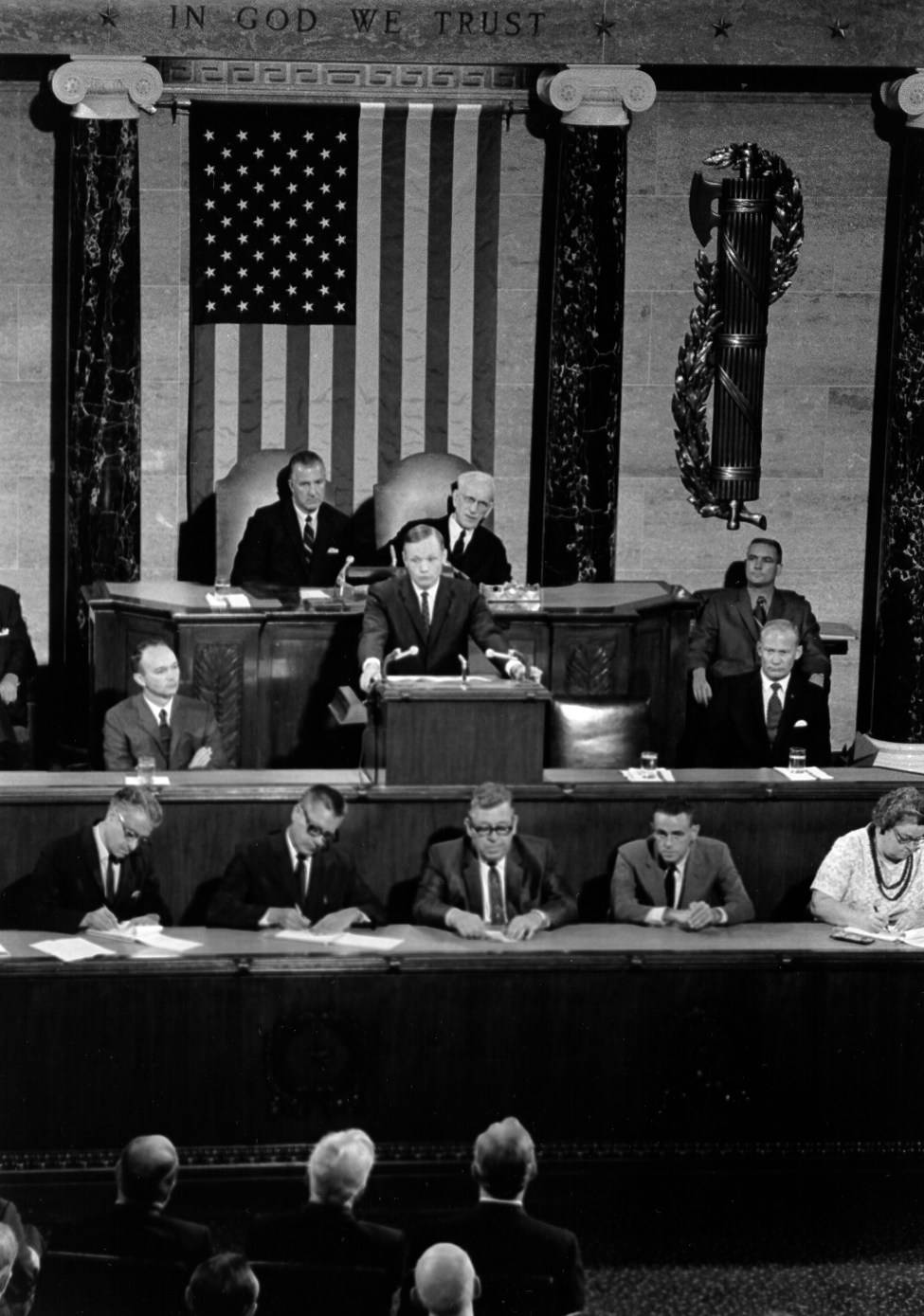

On May 25, 1961, when Kennedy asked Congress to send Americans to the Moon before the 1960s were over, NASA had no rockets to launch astronauts to the Moon, no computer portable enough to guide a spaceship to the Moon, no spacesuits to wear on the way, no spaceship to land astronauts on the surface (let alone a Moon car to let them drive around and explore), no network of tracking stations to talk to the astronauts en route.

“When [Kennedy] asked us to do that in 1961, it was impossible,” said Chris Kraft, the man who invented Mission Control. “We made it possible. We, the United States, made it possible.”

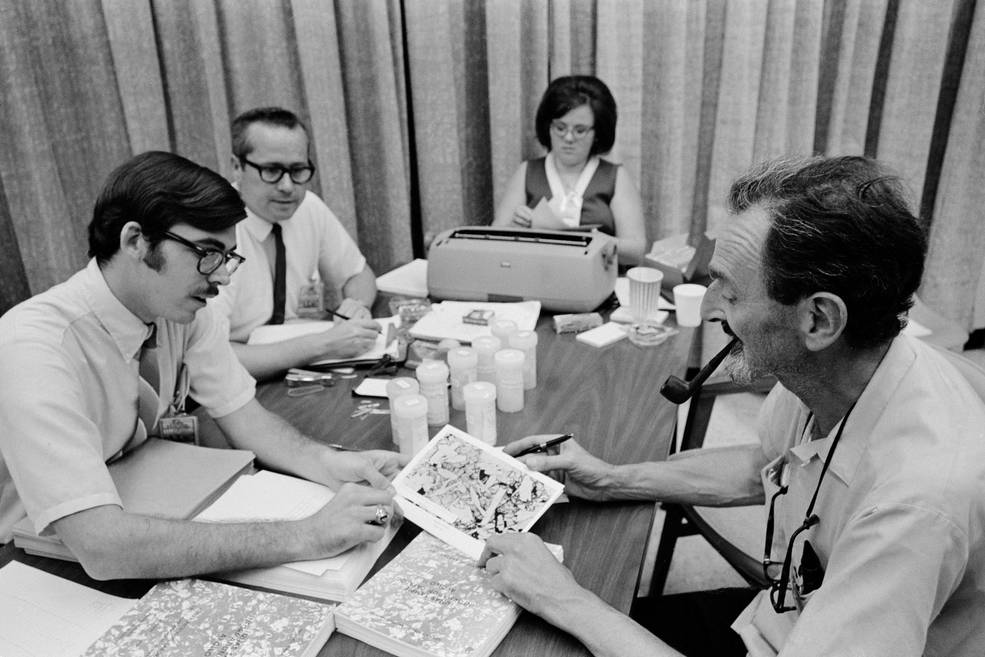

Ten thousand problems had to be solved to get us to the Moon. Every one of those challenges was tackled and mastered between May 1961 and July 1969. The astronauts, the nation, flew to the Moon because hundreds of thousands of scientists, engineers, managers and factory workers unraveled a series of puzzles, often without knowing whether the puzzle had a good solution.

One Giant Leap: The Impossible Mission That Flew Us to the Moon

In retrospect, the results are both bold and bemusing. The Apollo spacecraft ended up with what was, for its time, the smallest, fastest and most nimble computer in a single package anywhere in the world. That computer navigated through space and helped the astronauts operate the ship. But the astronauts also traveled to the Moon with paper star charts so they could use a sextant to take star sightings—like 18th-century explorers on the deck of a ship—and cross-check their computer’s navigation. The software of the computer was stitched together by women sitting at specialized looms—using wire instead of thread. In fact, an arresting amount of work across Apollo was done by hand: The heat shield was applied to the spaceship by hand with a fancy caulking gun; the parachutes were sewn by hand, and then folded by hand. The only three staff members in the country who were trained and licensed to fold and pack the Apollo parachutes were considered so indispensable that NASA officials forbade them to ever ride in the same car, to avoid their all being injured in a single accident. Despite its high-tech aura, we have lost sight of the extent to which the lunar mission was handmade.

The race to the Moon in the 1960s was, in fact, a real race, motivated by the Cold War and sustained by politics. It has been only 50 years—not 500—and yet that part of the story too has faded.

One of the ribbons of magic running through the Apollo missions is that an all-out effort born from bitter rivalry ended up uniting the world in awe and joy and appreciation in a way it had never been united before and has never been united since.

The mission to land astronauts on the Moon is all the more compelling because it was part of a decade of transformation, tragedy and division in the United States. The nation’s lunar ambition, we tend to forget, was itself divisive. On the eve of the launch of Apollo 11, civil rights protesters, led by the Rev. Ralph Abernathy, marched on Cape Kennedy.

In that way, the story of Apollo holds echoes and lessons for our own era. A nation determined to accomplish something big and worthwhile can do it, even when the goal seems beyond reach, even when the nation is divided. Kennedy said of the Apollo mission that it was hard—we were going to the Moon precisely because doing so was hard—and that it would “serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills.” And measure the breadth of our spirit as well.

Today the Moon landing has ascended to the realm of American mythology. In our imaginations, it’s a snippet of crackly audio, a calm and slightly hesitant Neil Armstrong stepping from the ladder onto the surface of the Moon, saying, “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” It is such a landmark accomplishment that the decade-long journey has been concentrated into a single event, as if on a summer day in 1969, three men climbed into a rocket, flew to the Moon, pulled on their spacesuits, took a few steps, planted the American flag, and then came home.

But the magic, of course, was the result of an incredible effort—an effort unlike any that had been seen before. Three times as many people worked on Apollo as on the Manhattan Project to create the atomic bomb. In 1961, the year Kennedy formally announced Apollo, NASA spent $1 million on the program for the year. Five years later NASA was spending about $1 million every three hours on Apollo, 24 hours a day.

One myth holds that Americans enthusiastically supported NASA and the space program, that Americans wanted to go to the Moon. In fact two American presidents in a row hauled the space program all the way to the Moon with not even half of Americans saying they thought it was worthwhile. The ’60s were tumultuous, riven by the Vietnam War, urban riots, the assassinations. Americans constantly questioned why we were going to the Moon when we couldn’t handle our problems on Earth.

As early as 1964, when asked if America should “go all out to beat the Russians in a manned flight to the Moon,” only 26 percent of Americans said yes. During Christmas 1968, NASA sent three astronauts in an Apollo capsule all the way to the Moon, where they orbited just 70 miles over the surface, and on Christmas Eve, in a live, prime-time TV broadcast, they shared pictures of the Moon’s surface, as seen out their windows. Then the three astronauts, Bill Anders, Jim Lovell and Frank Borman, read aloud the first ten verses of Genesis to what was then the largest TV audience in history. From orbit, Anders took one of the most famous pictures of all time, the photo of the Earth floating in space above the Moon, the first full-color photo of Earth from space, later titled Earthrise , a single image credited with helping inspire the modern environmental movement.

Anticipation for the actual Moon landing should have been extraordinary. In fact, as earlier in the decade, and despite years of saturation coverage of Apollo and the astronauts, it was anything but universal. Four weeks after Apollo 8’s telecast from lunar orbit, the Harris Poll conducted a survey and asked Americans if they favored landing a man on the Moon. Only 39 percent said yes. Asked if they thought the space program was worth the $4 billion a year it was costing, 55 percent of Americans said no. That year, 1968, the war in Vietnam had cost $19.3 billion, more than the total cost of Apollo to that point, and had taken the lives of 16,899 U.S. troops—almost 50 dead every single day—by far the worst single year of the war for the U.S. military. Americans would prove to be delighted to have flown to the Moon, but they were not preoccupied by it.

The big myth of Apollo is that it was somehow a failure, or at least a disappointment. That’s certainly the conventional wisdom—that while the landings were a triumph, the aimless U.S. space program since then means Apollo itself was also pointless. Where is the Mars landing? Where are the Moon bases, the network of orbital outposts? We haven’t done any of that, and we’re decades from doing it now. That misunderstands Apollo, though. The success is the very age we live in now. The race to the Moon didn’t usher in the space age; it ushered in the digital age.

Historians of Silicon Valley and its origins may skip briskly past Apollo and NASA, which seem to have operated in a parallel world without much connection to or impact on the wizards of Intel and Microsoft. But the space program in the 1960s did two things to lay the foundation of the digital revolution. First, NASA used integrated circuits—the first computer chips—in the computers that flew the Apollo command module and the Apollo lunar module. Except for the U.S. Air Force, NASA was the first significant customer for integrated circuits. Microchips power the world now, of course, but in 1962 they were little more than three years old, and for Apollo they were a brilliant if controversial bet. Even IBM decided against using them in the company’s computers in the early 1960s. NASA’s demand for integrated circuits, and its insistence on their near-flawless manufacture, helped create the world market for the chips and helped cut the price by 90 percent in five years.

NASA was the first organization of any kind—company or government agency—anywhere in the world to give computer chips responsibility for human life. If the chips could be depended on to fly astronauts safely to the Moon, they were probably good enough for computers that would run chemical plants or analyze advertising data.

NASA also introduced Americans, and the world, to the culture and power of technology—we watched on TV for a decade as staff members at Mission Control used computers to fly spaceships to the Moon. Part of that was NASA introducing the rest of the world to “real-time computing,” a phrase that seems redundant to anyone who’s been using a computer since the late 1970s. But in 1961, there was almost no computing in which an ordinary person—an engineer, a scientist, a mathematician—sat at a machine, asked it to do calculations and got the answers while sitting there. Instead you submitted your programs on stacks of punch cards, and you got back piles of printouts based on the computer’s run of your cards—and you got those printouts hours or days later.

But the Apollo spacecraft—command module and lunar module—were flying to the Moon at almost 24,000 miles per hour. That’s six miles every second. The astronauts couldn’t wait a minute for their calculations; in fact, if they wanted to arrive at the right spot on the Moon, they couldn’t wait a second. In an era when even the batch-processing machines took up vast rooms of floor space, the Apollo spacecraft had real-time computers that fit into a single cubic foot, a stunning feat of both engineering and programming.

Kennedy’s call to leap to the Moon ahead of the Russians was greeted with wild enthusiasm in the spring and summer of 1961. But when it came to public events, Americans’ attention spans were no longer in the 1960s than they are today. We were no more inclined toward the virtues of slow-and-steady progress, no more capable of delayed gratification. Even before 1961 was over, there were prominent public voices stoking skepticism and dissent about the value of the Moon race.

In 1961, Senator Paul H. Douglas released his own poll, not of the American people but of U.S. space scientists. The question: Was sending astronauts to the Moon, “at the earliest feasible moment,” of great scientific value? Douglas had arranged to poll the membership of the American Astronomical Society, and received 381 written replies from astronomers and space scientists. Of those, 36 percent said a manned Moon mission had “great scientific value,” and 35 percent said it had “little scientific value.” And unmanned, robotic missions to the Moon? Sixty-six percent of space scientists said they would have “great scientific value.” Douglas, a liberal Democrat, was a member of Kennedy’s own party, and he had gone to some trouble to establish that America’s actual space scientists judged that the race to the Moon wasn’t worth it. “If the astronomers are not competent [to decide],” asked Douglas, “who is?”

Norbert Wiener, a professor and legendary mathematician at MIT, dismissed Apollo in a late 1961 interview as a “moondoggle,” a word the press and NASA critics loved; through the end of 1961 and into 1962, “moondoggle” started to pop up regularly in coverage of the space program, particularly in stories about spending and in editorials.

In January 1962 the New York Times published an editorial pointing out that “the grand total for the Moon excursion would reproduce from 75 to 120 universities about the size of Harvard, with some [money] left over”—a Moon landing, or a Harvard University for every state?

In August 1962 the Russians launched two cosmonauts, in separate spaceships, within 24 hours of each other, the double mission totaling seven days in space at a moment when the total for all four American spaceflights was 11 hours. Kennedy was asked at a press conference why Americans shouldn’t be pessimistic since they were not just second to the Soviets but “now a poor second.” “We are behind and we are going to be behind for a while,” he replied. “But I believe that before the end of this decade is out, the United States will be ahead....This year we submitted a space budget which was greater than the combined eight space budgets of the previous eight years.” The press conference comments were defensive and reflexive. There was no eloquence about space in them, the responses more dutiful than enthusiastic.

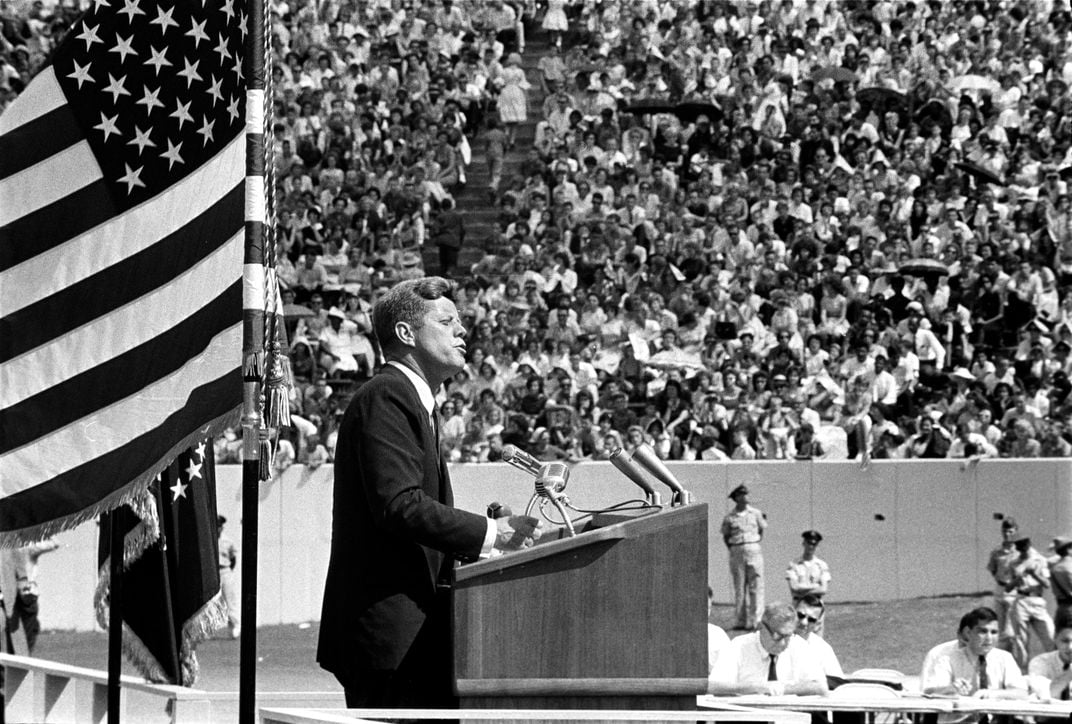

In the fall of 1962, Kennedy did a two-day tour of space facilities to see for himself how the Moon program was taking shape. Huntsville, Alabama, home to Wernher von Braun’s rocket team, was the first stop. Von Braun showed the president a model of the Saturn rocket that would eventually launch astronauts to the Moon. “This is the vehicle which is designed to fulfill your promise to put a man on the Moon by the end of the decade,” von Braun told Kennedy. He paused, then added, “By God, we’ll do it!”

Von Braun took Kennedy to the firing of a Saturn C-1 rocket as a demonstration of the coming power of American rocketry. The test—eight engines firing simultaneously, roaring red-orange rocket thrust out of a test stand, with Kennedy, von Braun and the visiting party in a viewing bunker less than a half-mile away—shook the ground and sent shock waves across the Alabama test facility. When the engines stilled, Kennedy turned with a wide grin to von Braun and grabbed his hand in congratulations. The president was apparently so captivated by von Braun’s running commentary that he took the rocket scientist—the biggest U.S. space personality outside the astronauts themselves—on the plane with him to Cape Canaveral.

At the cape, JFK visited four launchpads, including one where he got a guided tour from astronaut Wally Schirra of the Atlas rocket and Mercury capsule Schirra was set to ride into orbit in about two weeks.

Kennedy ended the day in Houston, where his popularity was on vivid display. The city’s police chief said 200,000 people—more than one in every five residents of Houston at the time—had come out to see the president, who rode in an open car from the airport to his hotel. Kennedy spent part of the next day at NASA’s temporary Houston facilities—the space center itself was under construction—including seeing a very early mock-up of the lunar module, then called “the bug.” But the emotional and political climax of Kennedy’s tour came Wednesday morning at the Rice University football stadium. In the blazing early-morning Texas heat—already 89 degree at 10 a.m., with Kennedy and his party wearing dress shirts, coats and ties—the president gave a speech designed to lift the space program up out of the political squabbles and budget bickering that was starting to beset it. “The United States was not built by those who waited and rested,” he said. “This country was conquered by those who moved forward—and so will space.”

Space didn’t just create the opportunity for knowledge and adventure, for American destiny and American values. It created an obligation to reach for the Moon, and to reach beyond.

That is the point of the most famous passage of the Rice University speech: “We choose to go to the Moon. We choose to go to the Moon....We choose to go to the Moon, in this decade, and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win, and the others, too.”

The Rice speech took place on September 12, 1962. Ten weeks later, on November 21, in the cabinet room, Kennedy presided over a meeting about America’s space program with a very different tone. It was fractious and frustrating, driven by the president’s own impatience. He didn’t like the slow pace of the program; he didn’t like what it was costing; and he didn’t like the answers he was getting from the people gathered around the table with him, including James Webb, the NASA administrator, and his most senior lieutenants.

Ostensibly the occasion for the meeting was to hash out whether NASA and Kennedy were going to push Congress for an extra $400 million for Apollo before the next budget cycle. Not even the NASA people agreed about the wisdom of that.

The poetry of the Rice speech, the vision of the future it expressed, is nowhere to be found in the cabinet room that Wednesday. We know this because, although the meeting was private, Kennedy had a secret taping system installed in the White House, as FDR had, as LBJ would, as Nixon, most famously, would.

The recordings preserve two high-level conversations about space that reveal a very different Kennedy attitude about the race to the Moon. At the first, just ten weeks after his Rice University speech, Kennedy spent 30 minutes asking questions about NASA’s budget and spending, trying to get to the bottom of the schedule. “Gemini has slipped how much?” he asked.

To much laughter—there were nine people in the meeting besides the president, four of them space agency people all too familiar with countdowns and launches that frequently slipped—Webb responded, “This word ‘slip’ is the wrong word.” To which Kennedy says, “I’m sorry, I’ll pick another word.”

Webb had been telling Kennedy that a Moon landing was possible in late 1967, but was more likely in 1968. Kennedy wanted it sooner. How do you move it back into 1967? Would the $400 million they were there to discuss do that? How about early 1967? What would that take? Kennedy seemed puzzled that more money wouldn’t necessarily make it happen sooner.

There is a long exchange in which Kennedy tries to understand why getting $400 million extra right now would help Gemini but wasn’t likely to move Apollo any sooner. He didn’t understand the details of staged technology development, that you have to build and fly Gemini in part to help you make the right decisions about Apollo. Four months here or there over four years is hard to nail down.

Thirty minutes into the conversation, the president takes a step back. “Do you think this program is the top-priority program of the agency?” Kennedy asked Webb.

“No sir, I do not,” Webb answered without hesitation.“I think it is one of the top priority programs, but I think it’s very important to recognize here—” Webb started to explain the importance of some of NASA’s non-Moon programs. Kennedy lowered his voice and simply stepped into Webb’s conversational stream.

“Jim, I think it is the top priority. I think we ought to have that very clear. This is, whether we like it or not, in a sense a race. If we get second to the Moon, it’s nice, but it’s like being second any time. So that if we’re second by six months, because we didn’t give it the kind of priority—then of course that would be very serious.”

The president was being as clear as he possibly could. It was fine to fly to the Moon, but the point of such urgency—the tripling of NASA’s budget in just two years—was to reach the Moon before the Russians. It didn’t seem clear to the people in the White House cabinet room that day, but the only reason they were there at all was that Kennedy needed to beat the Russians. Not because he needed to fly to the Moon.

“Otherwise, we shouldn’t be spending this kind of money, because I’m not that interested in space.”

The conversation continued well after Kennedy lost patience, and left. But no one took up, or even commented on, those arresting words, which must have been quite stunning to the space people in the room: I’m not that interested in space. The man who launched the United States to the Moon, “the greatest adventure on which man has ever embarked,” as he called it at Rice, just wanted to get there before the Russians.

In 1963 the politics of going to the Moon got even more challenging than they were in 1962. Webb was worried about the scientific community, many of whom felt that a space program that sent humans into space would consume huge amounts of federal money that could be used for scientific research with more immediate value on Earth.

In April, in an editorial in the prestigious journal Science , the editor, Philip Abelson, provided precisely the cerebral, almost disdainful critique Webb had been hearing in his conversations with scientists. Abelson walked through the justifications—military value, technological innovation, scientific discovery and the propaganda value of beating the Russians—and dismissed each in turn. “Military applications seem remote,” he wrote. The technological innovations “have not been impressive.” If actual science was a goal—and no scientist was on any imagined Moon landing crew yet—“most of the interesting questions about the Moon can be studied by electronic devices,” at about 1 percent of the cost of using astronauts.

As for the worldwide prestige, “the lasting propaganda value of placing a man on the Moon has been vastly overestimated. The first lunar landing will be a great occasion; subsequent boredom is inevitable.”

On June 10, Abelson was among a group of ten scientists called to testify, over two days, before the Senate Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences about the future of Apollo. Abelson, a physicist and a key contributor to the creation of the atomic bomb, told the senators, “[The] diversion of talent to the space program is having and will have direct and indirect damaging effects on almost every area of science, technology and medicine. I believe that [Apollo] may delay the conquest of cancer and mental illness. I don’t see anything magical about this decade. The Moon has been there a long time, and will continue to be there a long time.”

Two days later, former president Dwight Eisenhower spoke to a breakfast gathering of Republican members of Congress in Washington, where he was sharply critical of Kennedy’s spending plans overall. Asked about the space budget, Eisenhower replied, “Anybody who would spend $40 billion in a race to the Moon for national prestige is nuts.” The line drew sustained applause from the 160 Republican congressmen at the event. Leave aside that Eisenhower was going with the most extreme estimate of the Moon cost (one that didn’t come close to true in reality, even nine years later), that was the immediate past president of the United States calling the current president of the United States crazy. Headline writers from one side of America to the other loved the story, which made the front pages of dozens of newspapers with some variation of the headline “Ike Calls Moon Race ‘Nuts.’”

As it happens, on that day NASA announced the end of the Mercury program, the small capsules with just a single astronaut. Next up, the much more sophisticated, and much more ambitious, missions of Gemini. But the last Mercury flight was May 1963, and the first manned Gemini flight wouldn’t come until March 1965—a long time between “space spectaculars,” as Kennedy called them, to fire the public imagination, and enough time for an entire presidential and congressional election to play out without a single spaceflight.

In Congress, which was also thinking about elections coming the following year, NASA had gone from receiving near-unanimous support after Kennedy’s initial “go to the Moon” speech to being viewed as an agency where money might be harvested for other purposes.

As if to underscore the shift in public attitude, on September 13, 1963, the Saturday Evening Post , one of the widest circulation weekly magazines in the country, published a story titled “Are We Wasting Billions in Space?” On the cover the headline was just “Billions Wasted in Space,” without the question mark, a crisper summary of the story’s point. The Moon race, the story argued, had become a “boondoggle” and “a circus.”

The second recorded meeting that reveals Kennedy’s private thinking about space took place on September 18, 1963, in the Oval Office. Only President Kennedy and Jim Webb were present. On August 5, the United States, the USSR and Great Britain had signed a partial nuclear test-ban treaty, the first limits on nuclear weapons, and a major thaw in the Cold War. This meeting with Webb was long—46 minutes. The question was how to sustain Apollo during what were clearly going to be years of spending without years of excitement.

Right at the start, Kennedy said, “It’s been a couple years, and...right now, I don’t think the space program has much political excitement.”

“I agree,” said Webb. “I think this is a real problem.”

“I mean, if the Russians do some tremendous feat, then it would stimulate interest again,” continued Kennedy. “But right now, space has lost a lot of its glamour.”

The immediate cuts that congressional committees had proposed to the NASA budget would slow America’s leap to the Moon. Kennedy asked, “If we’re cut that amount...we slip a year?”

“We’ll slip at least a year,” replied Webb.

Kennedy: “If I get re-elected, we’re not going to the Moon in our period, are we?”

Webb: “No. No. You’re not going.”

Kennedy: “We’re not going...”

Webb: “You’ll fly by it.”

Webb was saying that, during Kennedy’s term, astronauts would fly around the Moon without landing, as Apollo 8 did, in fact, in December 1968, which would have been the end of the last year of Kennedy’s second term.

“It’s just going to take longer than that,” Webb said. “This is a tough job. A real tough job.”

It’s hard to listen to the conversation while setting aside everything we know that would come in the next ten weeks, and the next six years, and just imagine it from Kennedy’s point of view. This huge project he had set in motion. He wasn’t even done with his first term. Congressional critics weren’t just talking down the Moon landing; they were cutting the budget for the Moon landing. And Kennedy wouldn’t just have to muster the political support for Apollo through the election in a year; he was imagining having to sustain support for it through his entire next term, to which he hadn’t been re-elected yet. And even if he could do it, he wouldn’t enjoy the accomplishment during his own presidency.

It would have been a keen moment of disappointment, and you can hear it in Kennedy’s voice. It would also have been a moment of political calculation. How do you possibly hang on to a discretionary program of such enormous scale, already under fire, through four more budget cycles?

Just after that, Kennedy asked a version of the same question he had asked a year earlier: “Do you think the manned landing on the Moon’s a good idea?”

“Yes sir,” replied Webb. “I think it is.”

To Kennedy, the broader politics were simple and discouraging: “We don’t have anything coming up for the next 14 months. So I’m going into the campaign to defend this program, and we won’t have had anything for a year and a half.” He actually sounded disappointed, almost irritated by the timing of this flight gap. How could he talk with enthusiasm about space, when there were no spaceflights for anyone to be enthusiastic about?

In fact Kennedy saw only one strategy for protecting Apollo, an extension of the very first reasoning behind the Moon race. “I want to get the military shield over this thing,” he said, meaning, he wanted to be able to argue that manned spaceflight had explicit national security and defense value.

Webb went deep into the budget negotiations with Kennedy, talking about congressmen by name, but he also pulled back to remind the president of the incredible power of this kind of exploration and science for the life of Americans, for understanding how the world works, and also for the practical value of technology development, and for inspiring American students to pursue science and engineering. “The younger folks see this much better than my generation,” Webb said, having visited high schools and colleges around the country. He was talking about all the things that made Americans nervous after Sputnik, all the things Kennedy himself so forcefully argued in his Rice University speech. The lunar landing, said Webb, is “one of the most important things that’s been done in this nation.” What will come from going to the Moon will be “staggering things in terms of the development of the human intellect.”

The NASA chief concluded, “I predict you are not going to be sorry—ever—that you did this.”

On Thursday, October 10, 1963, the House passed the slimmed down $5.1 billion NASA budget—$600 million less than Kennedy requested, at least $200 million less than Webb had said was necessary to stay on track for a Moon landing within the decade. That seemed to be sending an ominous signal about the fading sense of congressional urgency and enthusiasm for reaching the Moon by the end of the decade.

So if John Kennedy had not been assassinated, would Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin have stepped off the ladder of the lunar module Eagle onto the Moon on July 20, 1969?

It seems unlikely.

President Kennedy visited Cape Canaveral for the third time, on November 16, flying up from where he was spending the weekend in Palm Beach, for two hours of briefings and touring. He got to see the Saturn I rocket on its launchpad, the rocket that would, a month later, finally put into orbit a payload larger than anything the Russians could launch. “It will give the United States the largest booster in the world and show significant progress in space,” the president said. The Saturn I was scheduled to launch in December; it ended up being launched successfully on January 29, 1964, sending ten tons into Earth orbit in a milestone considered so significant that the midday event was carried live by the TV networks.